To say that the gifting of the Felix Kelly Archive to Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki completes a 40-year process would overstate the matter only slightly. It is certainly true that it was 40 years ago that I chanced upon the book Paintings by Felix Kelly on the shelves of the University of Canterbury Library. Felix Kelly (1914–94) was unknown to me at the time, but I found the paintings fascinating. And I made two discoveries. Firstly, the publication revealed that the artist was a New Zealander. Secondly, I guessed (rightly as it turned out) that he was gay. It took me 10 years before I decided to research his career. To-ing and fro-ing between New Zealand and the United Kingdom for research over another 10 years led to publications on the artist, an exhibition that toured from Napier to Wellington and Auckland, and the accumulation of the body of material that is now deposited with the E H McCormick Research Library at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Dr Don Bassett

Article Detail

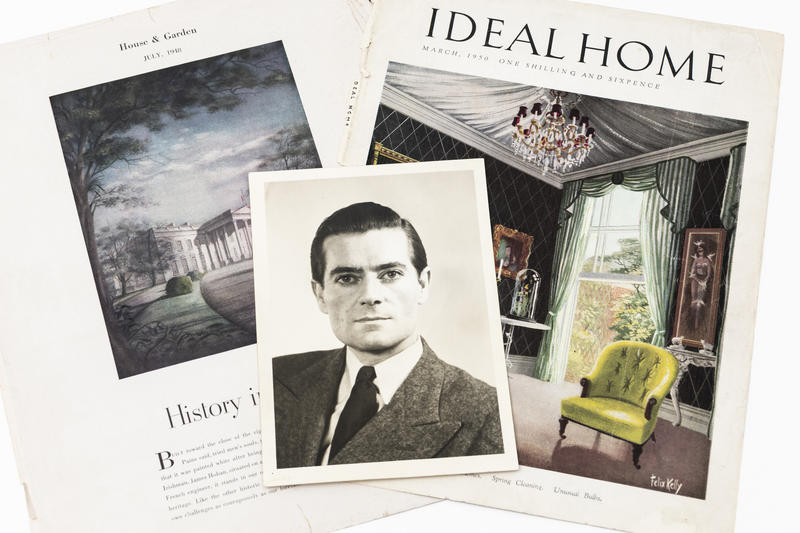

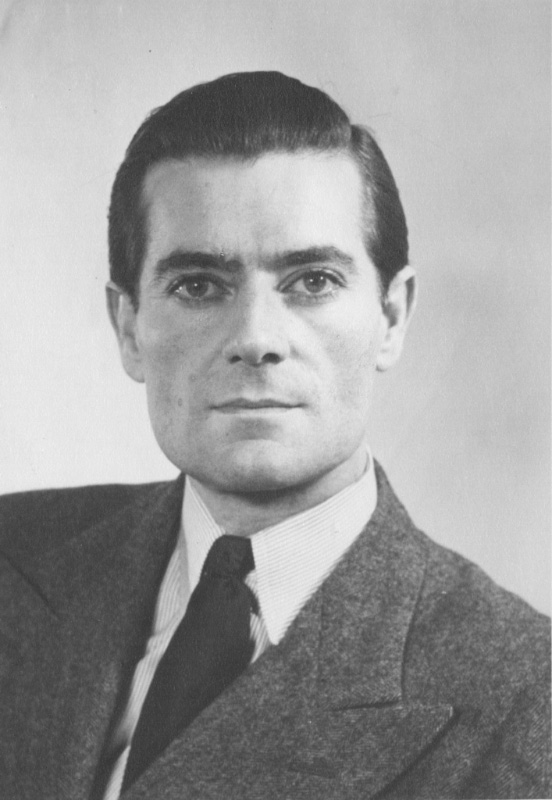

Unknown artist, Portrait of Felix Kelly, circa 1950. All artworks unless otherwise stated are from the Felix Kelly Archive, E H McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Don Bassett, 2022. All images unless otherwise stated are provided by Jennifer French and Paul Chapman

Kelly has been overlooked in the canon of our expatriate artists though his story seems to be unique – not that there weren’t plenty of gay and lesbian artists from here who set up overseas, but his life, his associates, his subject matter, and the sheer breadth of his artistic activity are unparalleled in our art story even if his is in one sense a not unusual gay one. Kelly was born and grew up in Auckland. At 21 he had fled this country for London, never to return. He needed to get away. In London he found greater social and sexual acceptance in the anonymity of a big city, and the cultural richness Europe offered eclipsed anything he had experienced here. Europe fed the dreams nurtured by his typically Eurocentric education.

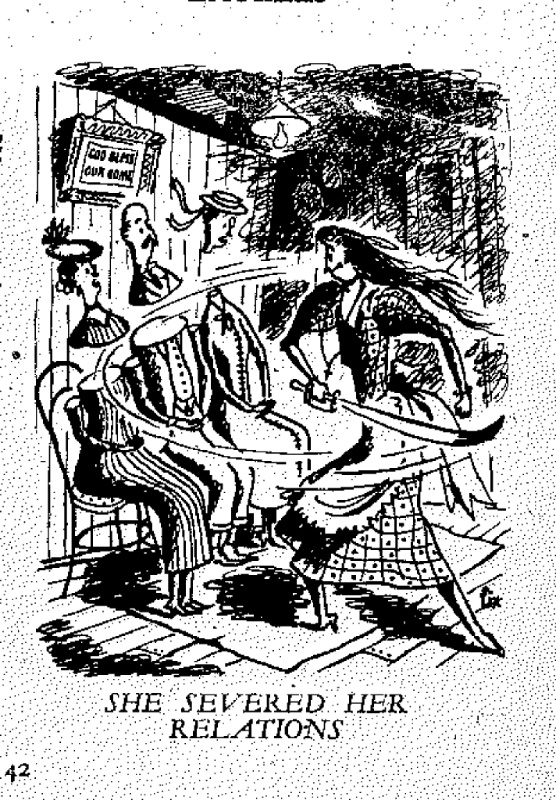

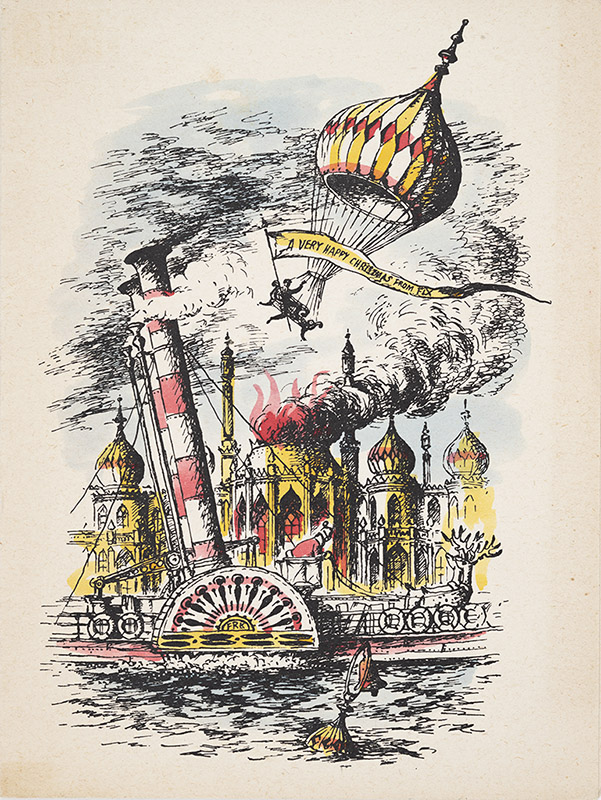

On arrival in Britain, he embarked on a career as a graphic artist at Lintas (an agency of the Lever Brothers), working on advertisements for soaps and cosmetics. While his ambition was to make a career as a painter, his first 20 years in England found him working in a range of graphic and design fields. The archive contains material from the late 1930s and 40s when, as a side-line to his work as a layout man, he contributed cartoons to the popular magazine, Lilliput, and illustrations for journals such as The Aeroplane and The Motor. In these he revealed his love of motor transport, both ancient and modern (he drove fast cars and sought out steam fairs and vintage railways). In this work he revealed his sense of humour – Kelly was an asset at smart dinner parties for the sharpness of his wit.

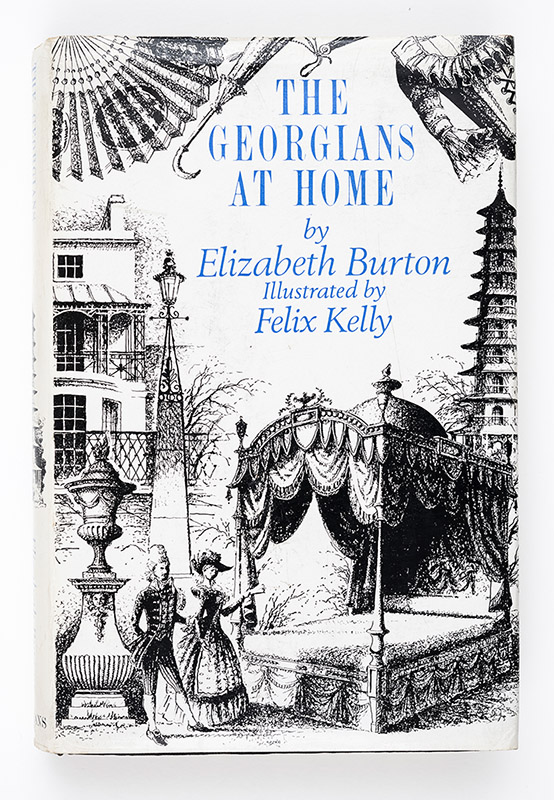

At this time, he also supplemented his income by designing dust jackets for books. The archive contains several examples of this work, his neo-Rococo style easily recognisable on books ranging from thrillers and bodice-rippers to serious history. Kelly also illustrated numerous books, including the English history series Elizabethans at Home and Jacobeans at Home written by his friend, Elizabeth Burton, a complete set of which is in the archive. In the same vein (sometimes high camp), he designed his own greetings cards.

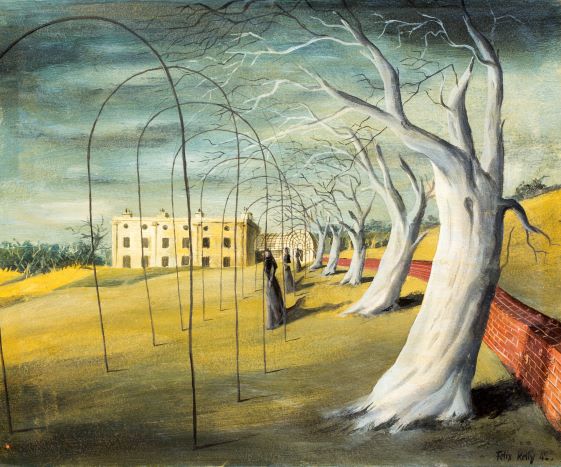

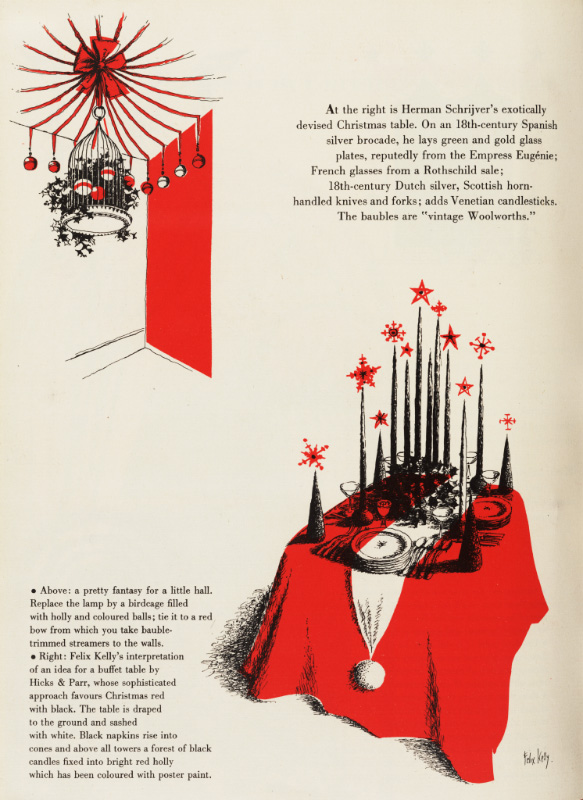

Architecture was a central element in his work. His graphic art of the 1950s included contributions to fashionable magazines like House and Garden and Harper’s Bazaar on interior décor, suggestions for makeovers and so on, usually in the Regency style. He had developed an early interest in buildings from his father, an engineer and surveyor in Auckland, but his arrival in Britain steered his interest towards historic architecture, assisted in no small way by his growing association with the British upper classes. How he ‘broke into’ high society (something gay men have often striven for in a bid to counter the negativity experienced in their youth) is debateable, but shared interests in cars and model railways – as well as the bedroom – seem likely routes. By the 1940s Kelly was a regular at country-house weekends, and, as the 1946 book Paintings by Felix Kelly attests, old houses, frequently Georgian, recur in his work.

Felix Kelly, Designs for Christmas decoration, table setting by Hicks & Parr, Harper’s Bazaar, 1958

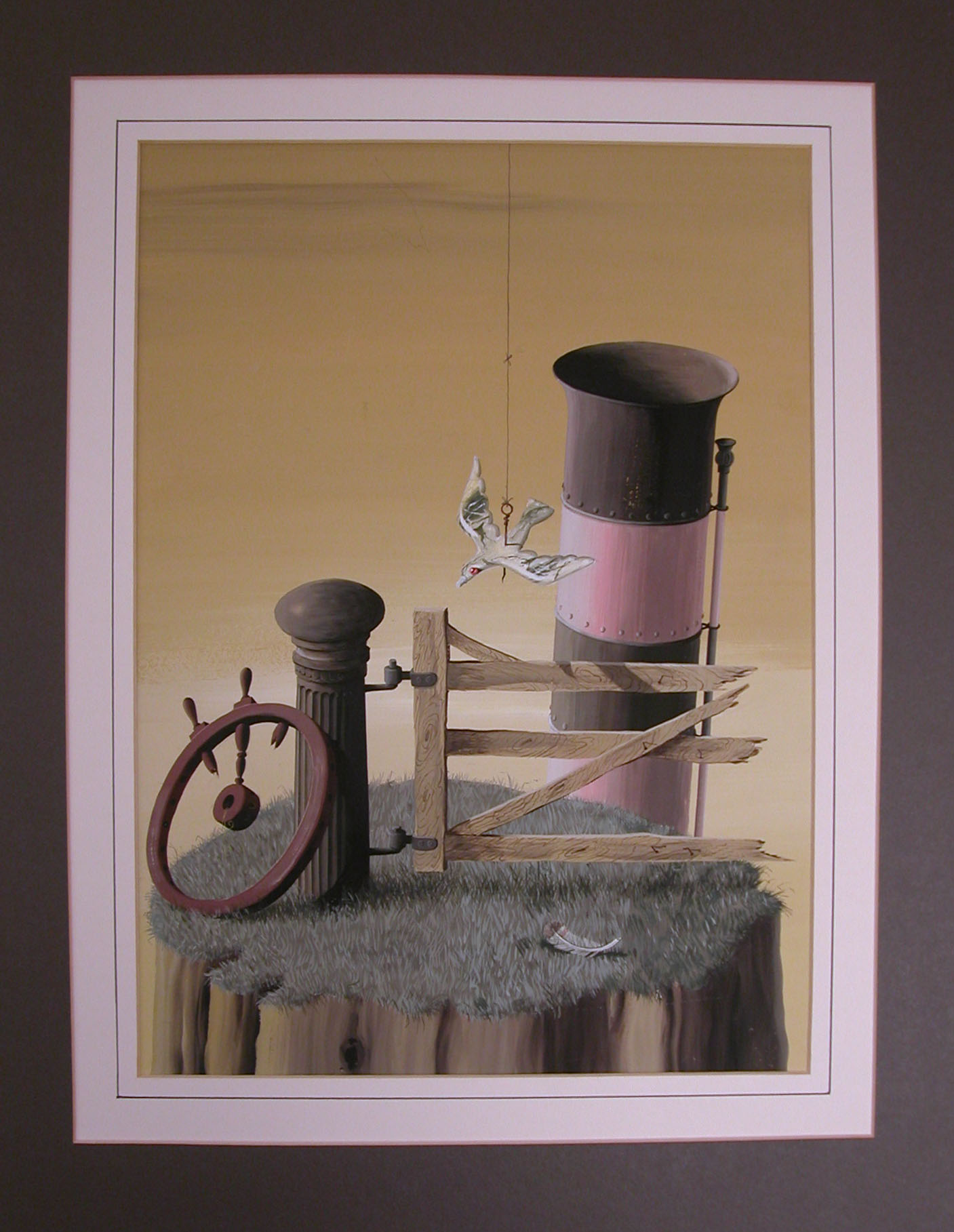

Upon arrival in England in the 1930s, Kelly dabbled with Surrealism in a rather camp sort of way. A couple of rather good – and amusing – pictures in this vein are now in the collection of the MTG Hawkes Bay. But as rich friends and clients increasingly asked for ‘portraits’ of their houses, Kelly’s work took a new direction. The best paintings combine fantasy elements with tinges of his earlier Surrealism, rather than straight portraits of the houses (though he did these too, and they are not exciting). Dilapidation and a sense of the weird animate his better work, a development which aligns him with the neo-Romantic movement and the work of British artists such as John Piper and Keith Vaughan (whom he knew) as well as our own Frances Hodgkins. It was certainly a coup that Kelly attracted the interest of renowned English art historian Herbert Read, who bought one of his best paintings, Three Sisters, 1943 (now in the collection of the University of Auckland), from Kelly’s first exhibition at the prestigious Lefevre Gallery in Mayfair in 1943.

The Felix Kelly Archive at Auckland Art Gallery documents the remarkably diverse outputs in Kelly’s career, many of which are now lost. An important part of the archive is a large number of old photographic prints and negatives. Kelly kept a photographic record of his paintings from the 1940s onwards. In many cases the location of these works is unknown. These high-quality images are the only evidence we have of the paintings until such time as the originals show up at auction houses, and as such have considerable value.

The photographs in the archive also provide a record of Kelly’s stage designs and his murals. For a 10-year period from the mid-1950s, Kelly designed a number of West End productions starring the likes of Gielgud, Olivier and Thorndyke. Reviews of these productions and his exhibitions were assiduously collected by the artist himself, as were accounts of murals he executed for private houses and for public locations ranging from ocean liners to a London ice-skating rink. These and other cuttings from periodicals and newspapers are amongst the papers preserved.

Felix Kelly, Stage design for Sir Lennox Berkeley’s opera Nelson, 1954, transparency of a painting in the collection of the Berkeley family

Several times during his career Kelly made trips to the United States of America, exhibiting in New York and other centres. Just as he had built up a clientele – and a circle of friends – amongst the British upper classes, so too did he cultivate friendships amongst rich Americans, especially in the Deep South. (Politically, Kelly was undoubtedly a Tory.) The R W Norton Art Gallery in Shreveport, Louisiana, established by the family of a wealthy oil-field discoverer, has an extensive collection of his American paintings from the 1960s onwards.

By the 1970s his acquaintance included royalty, who attended the openings of his exhibitions at the preferred dealer gallery of his late career, Partridge Fine Art in London. Most significant was his association with the Prince of Wales, who commissioned Kelly to work on the remodelling of Highgrove. With his extensive knowledge of pre-modern British architecture, the artist created in oils an imagined version of the original 18th-century house that had undergone unfortunate alteration in the following century. Prince Charles liked the idea of ‘restoring’ the house and Kelly worked with architects to bring about the transformation. Other houses enjoyed his attention in a similar way. Material relating to this activity is in the archive.

Felix Kelly, New Zealand River Scene, 1962, transparency of oil painting in private collection, England

It is true to say that Kelly’s later painting lost its sharp focus and its wit, becoming somewhat formulaic. There is a lot of fairly uninteresting work in this late period as Kelly responded to the taste of his conservative patrons. Unfortunately, this period came to overshadow his earlier work and insofar as New Zealand knew of this artist at all, it was this phase with which his name became associated. Moreover, it is clear that he infringed cherished notions of ‘New Zealandness’, further ensuring his exclusion from our national story: he courted the aristocracy, he was homosexual, and after emigrating he never returned. But during the 30 years following his departure he continued on occasion to paint pictures – fantasies – of the New Zealand he left behind. These became decreasingly like the real thing, inflected as they were by what he had seen when away and what he wanted his home country to be. I believe that Felix Kelly’s career and overall oeuvre constitute an important addition to the story of Kiwi expatriate art

-----------------------------

Dr Don Bassett is former Senior Lecturer, Art History, at the University of Auckland. He has written several publications about Felix Kelly, including the 2006 book Fix: The Art and Life of Felix Kelly, and curated the exhibition Felix Kelly: A Kiwi at Brideshead, which was developed and toured by MTG Hawkes Bay in 2009 and then toured to The Dowse and Gus Fisher Gallery.

Felix Kelly Archive

E H McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Don Bassett, 2022

RC2022/3