Thursday 20 March 2014

Rhana Devenport

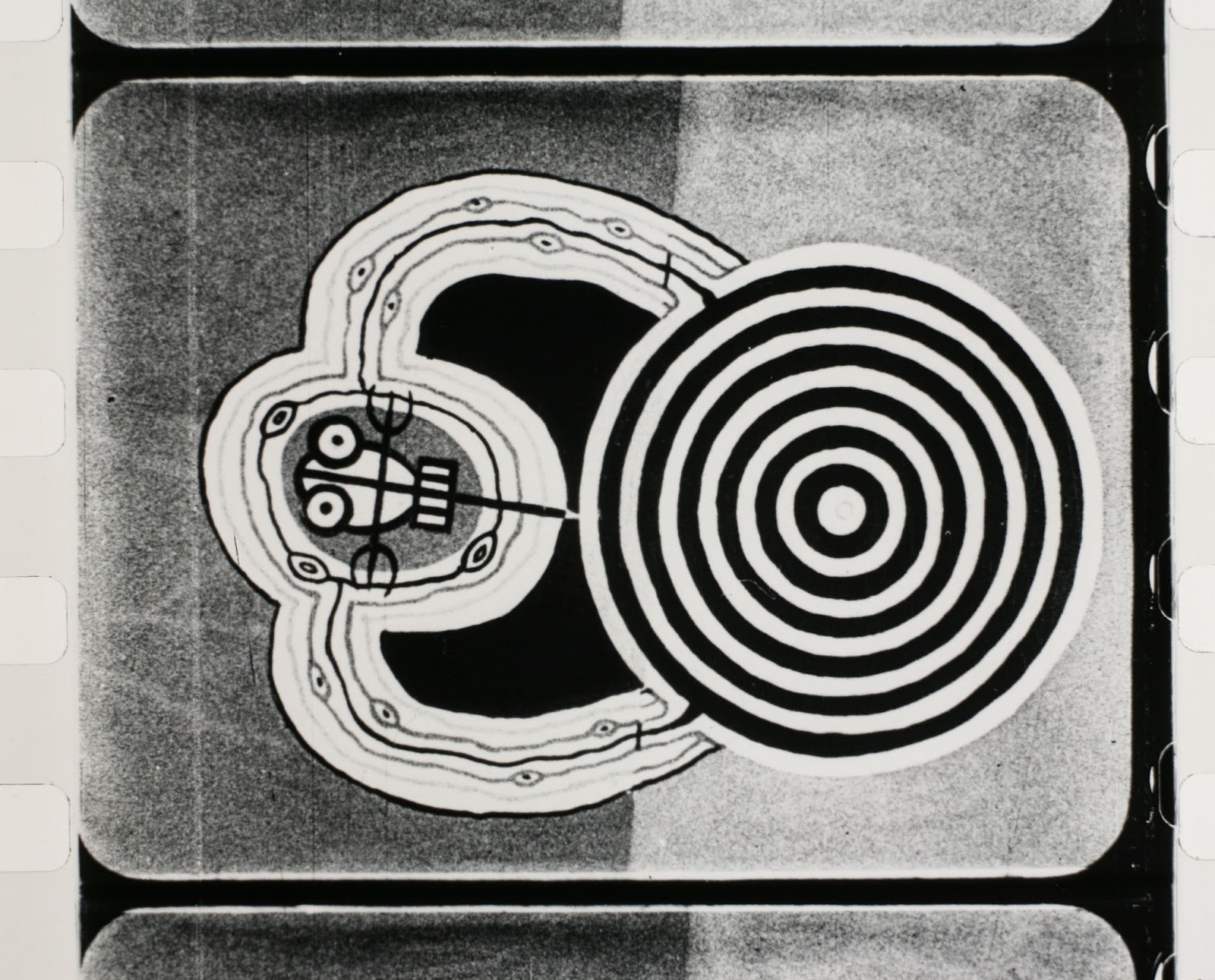

Len Lye, Tusalava, 1929 (film still). Courtesy of Len Lye Foundation from material preserved and made available by the New Zealand Film Archive Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Taonga Whitiāhua.

On 15 March at Mangere Arts Centre – Ngā Tohu o Uenuku, I was fortunate to witness a fascinating performance that expands contemporary inter-disciplinary arts practice in Aotearoa while re-energising our consideration of one of New Zealand’s most influential and maverick artists. Here is the back-story . . . when Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki re-opened in 2011, the Whizz Bang Pop exhibition included Len Lye’s Universe, 1963 from the Edmiston Trust Collection, not surprisingly the work quickly became a beacon for visitors who were captivated by its fluid, sexy movements and quirky self-generating soundscape. Triggered by electro-magnets and informed by the artist’s audacious experimentations with movement, Universe remains one of Lye’s most beautifully resolved sculptural works. Two other versions exist in public collections, one in the Len Lye Foundation’s collection at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery and the other, a smaller table top version entitled Loop (the work’s original title, until a child suggested Universe to the artist), at the Chicago Art Institute.

Len Lye, Universe, 1963, steel, wood, electromagnets, Edmiston Trust Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1995

However, Lye did not begin making his kinetic sculptures, or ‘tangibles’ as he called them, until the late 1950s. It was, of course, in experimental film where he first made major contributions to 20th-century art practice. His very first film is the much-celebrated Tusalava, 1929, a 10-minute stop-frame animation comprising around 7000 black and white drawings. The work is exceptional for its time, given Lye’s respect for and influence from Indigenous Pacific cultural practices. He greatly admired Māori sculptural and patterned forms while studying design in Wellington, when in Sydney from 1922 he researched Aboriginal art and philosophy and during his stay in Sāmoa during 1924, became fascinated with tapa. Tusalava is a remarkable and radical distillation of modernism within a located Pacific sensibility. The original film score by the Manchester-born Jack Ellitt (a somewhat forgotten pioneer of 20th-century electronic music) was lost and over the years various musicians have created unsolicited or commissioned scores for the film. The most recent, until now, was by British jazz pianist Alcyona for the 2008 Len Lye: The Body Electric exhibition at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. For Len Lye: Chronosome in 2009 the Govett-Brewster presented three versions of existing scores in sequence within the exhibition, interestingly each was composed to a different print/version of the film and were subsequently run at a slightly different speeds. The film was also presented on a two-sided screen as it had, at one stage previously, been screened in reverse.

Like Lye, Ellitt was living in Sydney in the early 1920s and was part of a thriving ‘Bohemian’ arts community. Like Lye he had embarked upon a project of radical intent in relation to technology and the synergy between art forms and an embrace of the modern that was also filtering across from Europe. Ellitt spoke of ‘sound colours’ and a release from conventional notions of harmony and melodic structures. After Lye moved to London in 1926, Ellitt followed and the two men continued their creative friendship in London (where they lived on a barge for while) in the circle of Robert Graves and Henry Moore. When Lye finally completed Tusalava in 1929, it was Ellitt who wrote the score. With no extant recording, Len Lye biographer Roger Horrocks believes the score was probably in the realm of Stravinsky’s two piano version of The Rite of Spring or Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique for two pianos.

Around two years ago when I was director of Govett-Brewster, James Pinker approached the Gallery and the Len Lye Foundation with the concept of an exhibition exploring Lye’s profound connection with Pacific Indigenous practices. The idea was long overdue and much needed, and it seemed perfect that the project would be occurring in South Auckland.

Len Lye: Agiagiā, an articulate and significant exhibition, curated by Pinker and Paul Brobbel, has been presented at Mangere Arts Centre over the past three months and the performance on the eve of its final day was an inspired and important occasion. It draws its name from a Sāmoan word expressing the notion of ‘natural billowing movement’. Pinker commissioned three Pasifika composers to create scores to accompany Tusalava. Very simply, the evening saw the three scores played consecutively alongside the film, while a lively discussion with the composers and the audience followed the screenings.

Left to right: Poulima Salima, Anonymouz and Opeloge Ah Sam in conversation with James Pinker, co curator of Len Lye: Agiagiā. Photo credit: Anna Rae

Matatumua Opeloge Ah Sam, Poulima Salima and Matthew Faiumu Salapu aka Anonymouz are all strongly connected to Mangere and Sāmoa. Their scores were remarkably different in mood and approach and as each were played, the visual reading of the film shifted profoundly. It was an extraordinary experience. Matatumua Opeloge Ah Sam’s score is joyous and energised; it begins with the beating of the fala (mat in Sāmoan) a sound element that remains present throughout the composition. Ideas about weaving and organic flow, and the positive themes of life, growth and development that Opeloge Ah Sam read in the film informed his treatment. A vocal enters the score in the final stage; the word is matagofie (beautiful). In contrast, Poulima Salima created a dark soundscape that concentrates on his interpretation of the destructive elements that enter the film. It begins with a sample of a projector sound over the titles and soon launches into a work of brooding symphonic beauty. Poulima spoke about Lye being ‘light years ahead of 1929’ and this drove his own urgency to expand his approach and push himself into new compositional terrain, what he described as ‘pushing sound design as landscape’. Finally, Matthew Faiumu Salapu drew on his three modes of working: composer, hip-hop producer and sound engineer, to create a complex spatial work. Faiumu Salapu echoed Lye’s scratching of celluloid (in his later films) with audio scratching while gathering in Maori, Samoan and Australian Aboriginal instruments. The didgeridoo, for example, was present throughout the entire piece at a very low frequency and it was only in the final moments that its sound became audibly distinctive. Faiumu Salapu spoke about how Lye extended the parameters of available technology and that his own intensive engineering of site recordings that he made in Sāmoa was a way to honour and continue this strategy. All three composers spoke about being true to Lye’s stellar imagination and uncompromising and tireless approach to experimentation and the testing of boundaries.

New Compositions – Tusalava is a project that spans two centuries and connects the radical work of a spirited cultural innovator – who was himself greatly influenced by Pacific cultural modes – to today’s moment of intense cross-cultural and cross-temporal influence. The project has not come full circle, 85 years later in an act of reclamation; rather Lye’s Tusalava has become a launching pad for unexpected points of reference and the subtle sensibilities of these three impressive, insightful and wholly generous composers. The process is not circular but expansive.