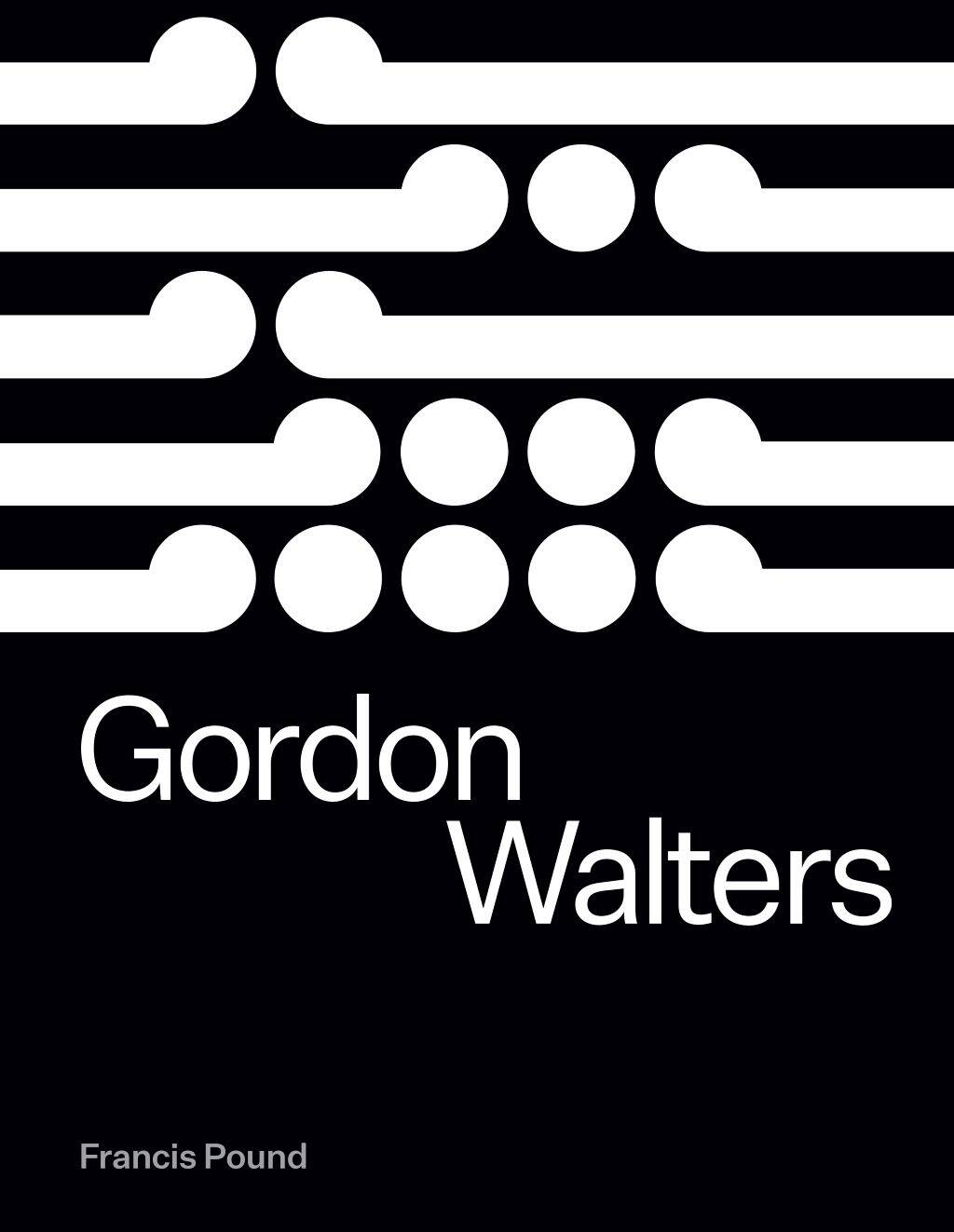

Last week, Auckland University Press launched Gordon Walters, a substantial monograph on the art of one of this country’s most influential artists, researched and written by Dr Francis Pound (1948–2017) over the course of more than a decade. After Pound's death in 2017, Leonard Bell was tasked with stewarding his friend’s manuscript for publication. In the article, he reflects on how this book, published six years after Pound’s death, came to be.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The last paragraph of Francis Pound’s (1948–2017) preface to his book, The Invention of New Zealand: Art and National Identity 1930–1970 (2009) reads:

Finally, on the matter of the apparently excessive time [23 years] taken in completing this book, there is the seldom acknowledged fact of the sheer happiness of writing. Writing this work was, for all those years, simply what I did in my days and my nights. In some way, it justified me – or, at least, removed all uncertainty about what to do in the hours remaining in a day or a life. Already, it has been many books. Why ever, then, bring it to an end?[1]

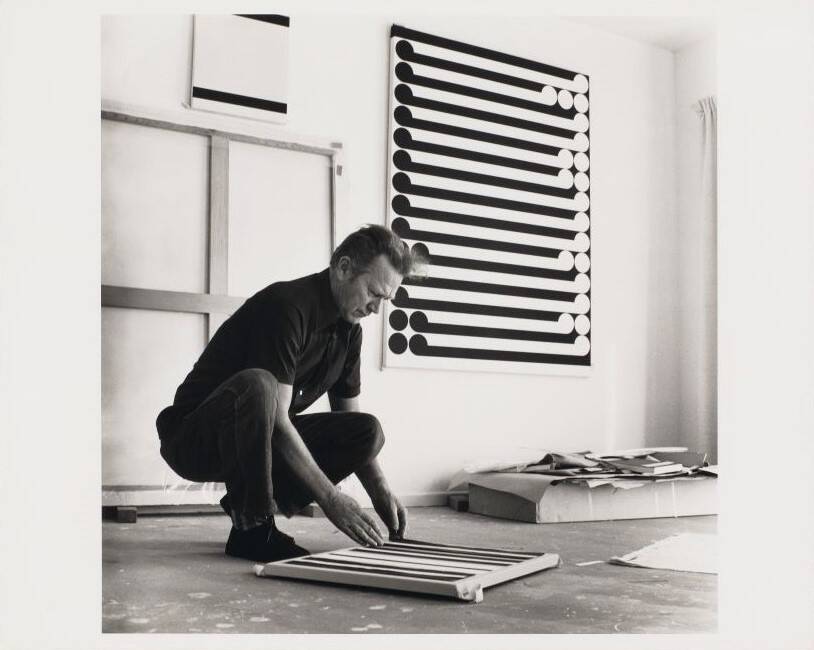

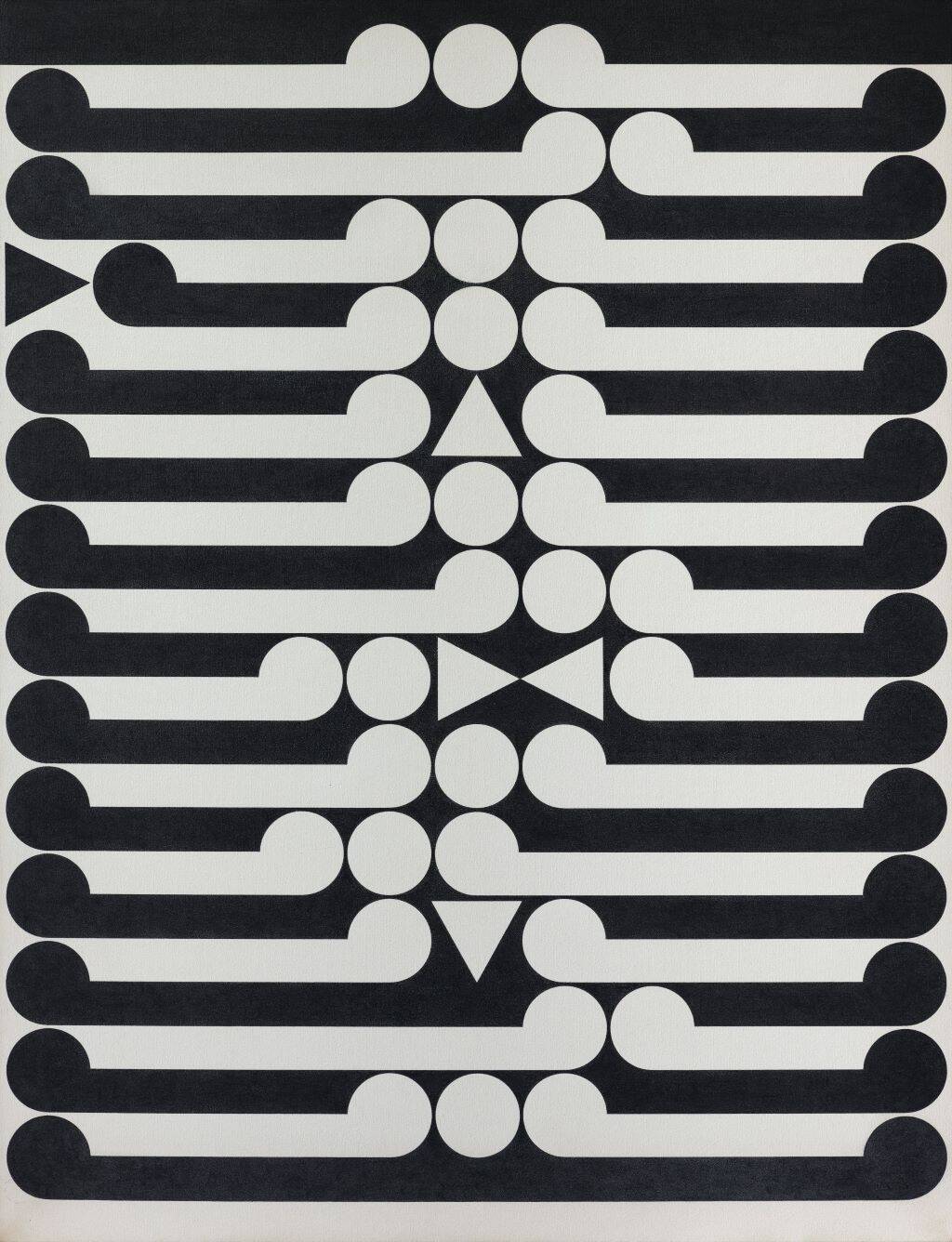

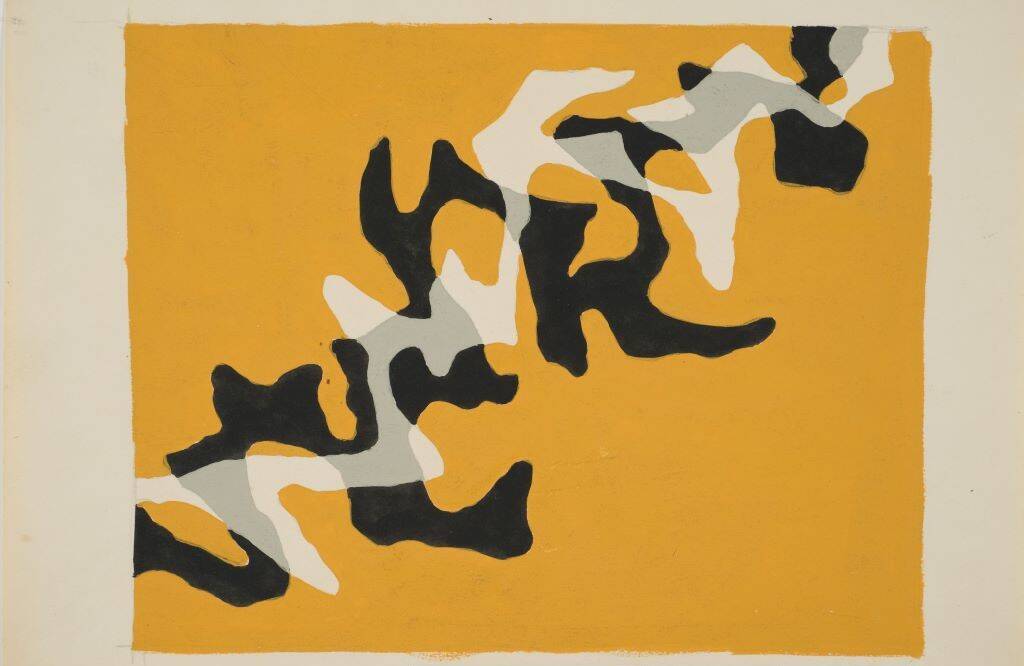

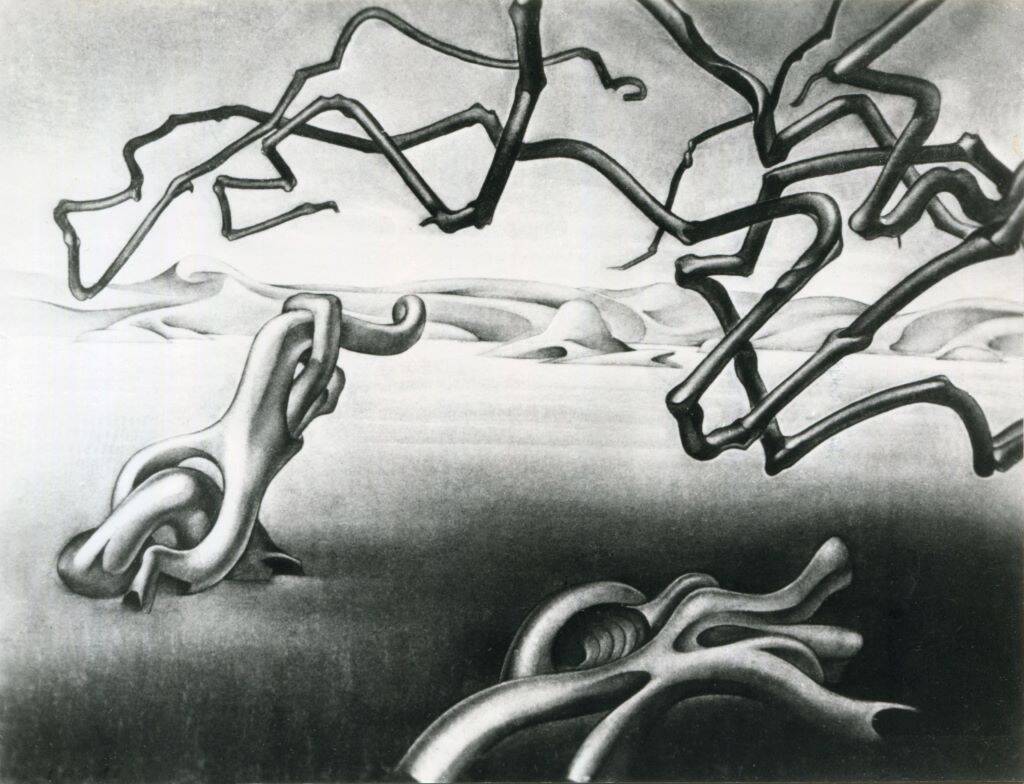

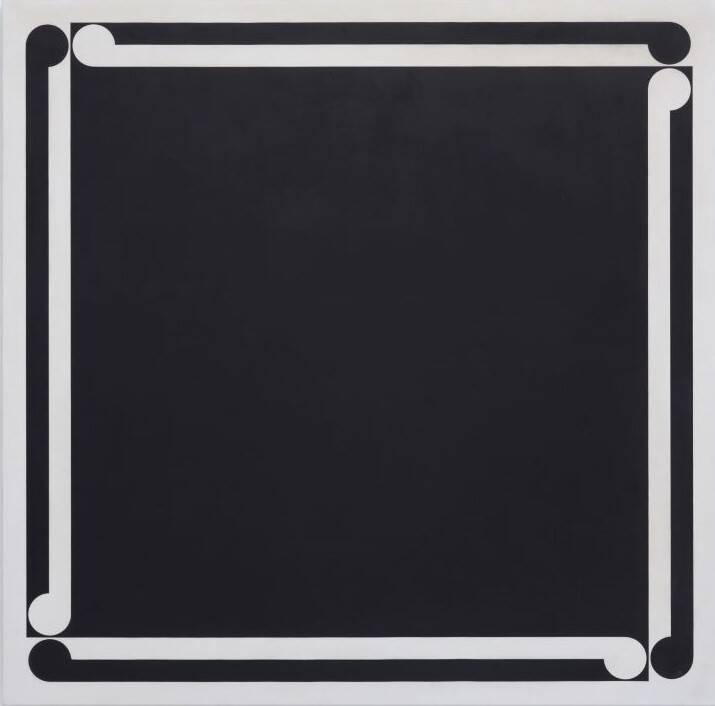

Unfortunately those days and nights ran out, and his manuscript for what became Gordon Walters, for which he had been researching since the early 2000s, was unfinished, only completed and prepared for publication after his death. That was my task, with the help of copy and production editors. Like its predecessor (446 pages), Gordon Walters is not a short book. It comes in at 464 pages, including a wonderful 430 images (comprising reproductions of works by Walters and other artists, photographs, book covers, etc).

![<p>Gordon Walters, <em>Untitled [Composition]</em>, 1955, gouache and pencil on paper, Collection of Richard Killeen and Margreta Chance</p>](https://cdn.aucklandunlimited.com/artgallery/assets/media/gordon-walters-untitled-composition-1955-resized.jpg)