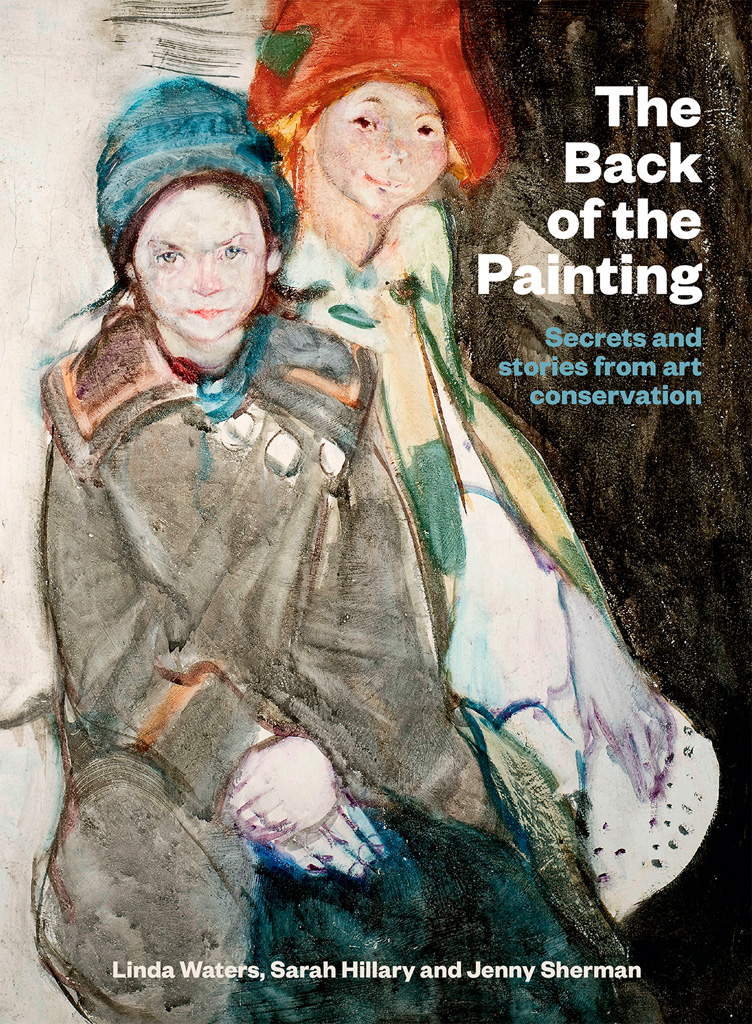

In the spring of 2019, Linda Waters, paintings conservator at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Jenny Sherman, conservator at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, and I met to discuss The Back of the Painting book project. We have all had long and interesting careers working on diverse collections and had known each other for some time: Linda and I had studied conservation at the University of Canberra together in the early 1980s before she eventually took on a painting conservation position at the National Gallery of Victoria; and I had met Jenny when as a conservator she had couriered the Rembrandt to Renoir exhibition to the Gallery from The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in 1993, before she moved back to New York to private practice and teaching at New York University. We had all ended up working in public art galleries around New Zealand and kept in regular contact. Because of our different backgrounds, each of us approached this book project slightly differently, with a focus on Old Master paintings (pre-1800) by Jenny, and for Linda and me, 19th-century and later.

To conservators, paintings are not merely the image on the front, which is so frequently reproduced. Instead, we see paintings as three-dimensional objects that reveal their materiality and unique histories. It is the backs of paintings, which are often hidden, that can contain important information and contribute to our understanding of them as works of art, as well as informing the approach we end up taking to their treatment and care. The Back of the Painting was an opportunity to share some of our observations and discoveries and to give a sense of what a wonderful privilege it is to be working so closely with works of art.

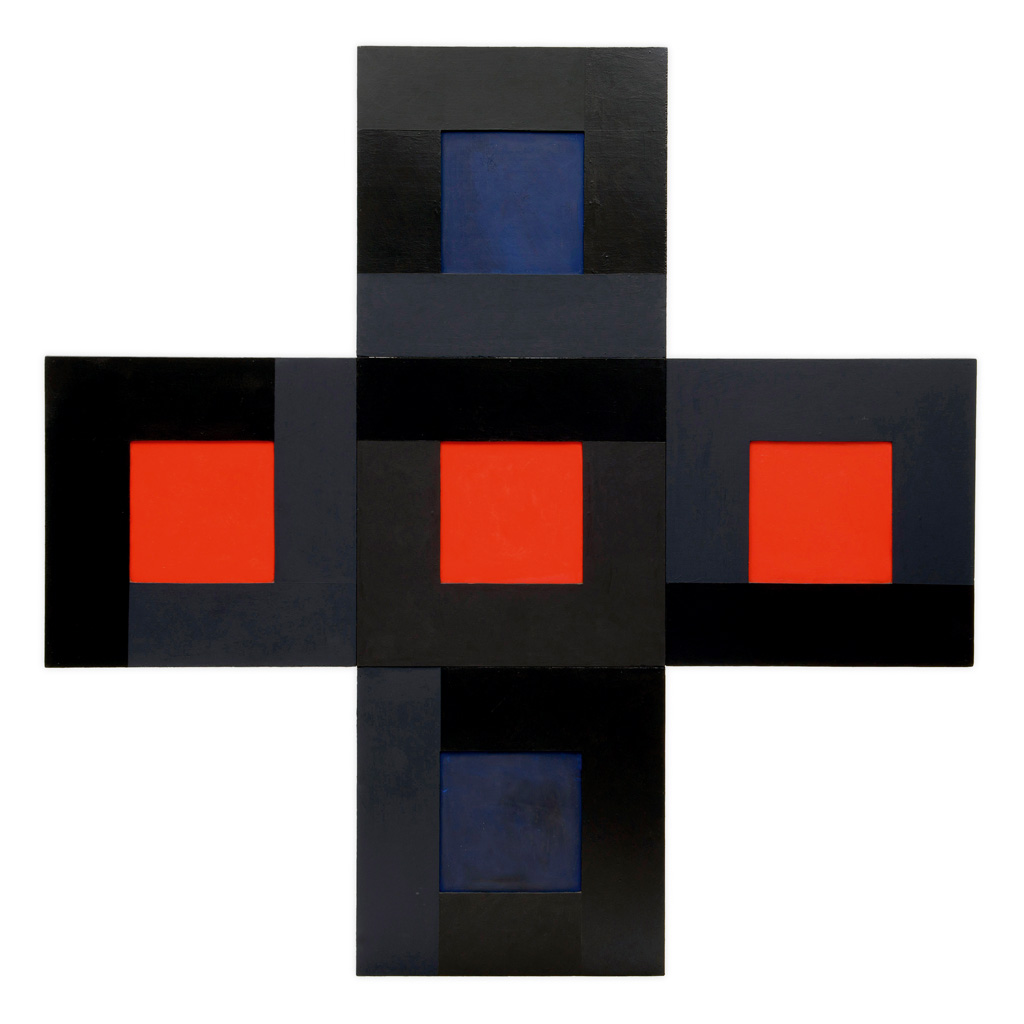

Long Red Line, 1964 by Ralph Hotere, seemed an obvious candidate for me to include in the book because of the significance of the materials used to make up the structure, which are only clearly identifiable from the reverse. In a conversation with Ralph Hotere, late in his life, we discussed this and other works from his Human Rights series and he described how he had used the packaging for televisions found in a London dump to make the painting structures.[1] Their significance had been so great that Hotere brought them all the way back to New Zealand. Friend and dealer Rodney Kirk Smith recalled that in 1965: ‘He disembarked from the boat carrying strangely painted luggage which turned out to be works of art he had nailed together to make them portable.’[2] This included Long Red Line, which is now part of the Chartwell Collection at the Gallery.