In 1964 the population of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland reached the half-million mark in the same month that Beatlemania hit our shores with the Fab Four touring New Zealand to the screaming adulation of tens of thousands of teen fans. In a moment, youth culture had become headline news on television and the front pages of the country’s newspapers, marking the tremors of our own local youthquake. In the same year, Isobel Haworth opened Hadny 5 boutique on Swanson Street, Auckland, Wendy Ganley opened her Elle Boutique in Hamilton, and Jennifer Goodward of Jennifer Dean Boutique in Auckland’s Vulcan Lane showed a topless bathing suit in a public fashion parade. Diane Lee became Dinah Lee, and released her debut single, ‘Don’t You Know Yockomo?’, Ray Columbus and the Invaders recorded ‘She’s a Mod’, and both became smash hits here and in Australia. Although the term ‘youthquake’ wasn’t quite in common usage – being first coined in 1965 by Diana Vreeland, editor-in-chief at Vogue magazine – the phenomenon wasn’t new because the young should and have always shaken the foundations of society.

Doris de Pont

Article Detail

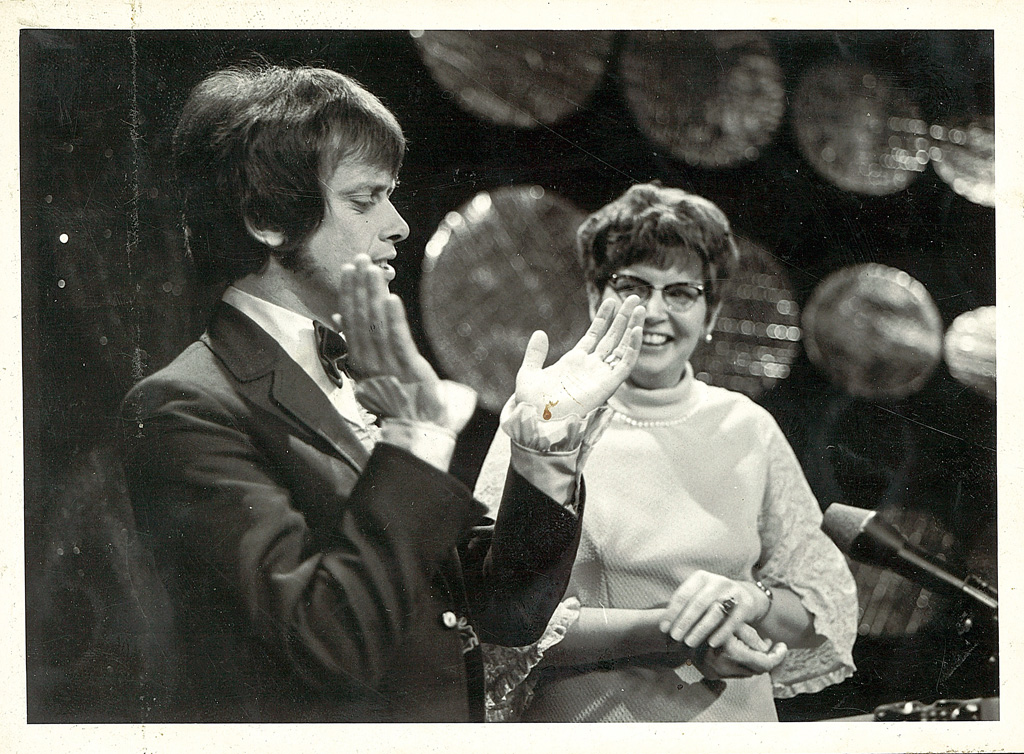

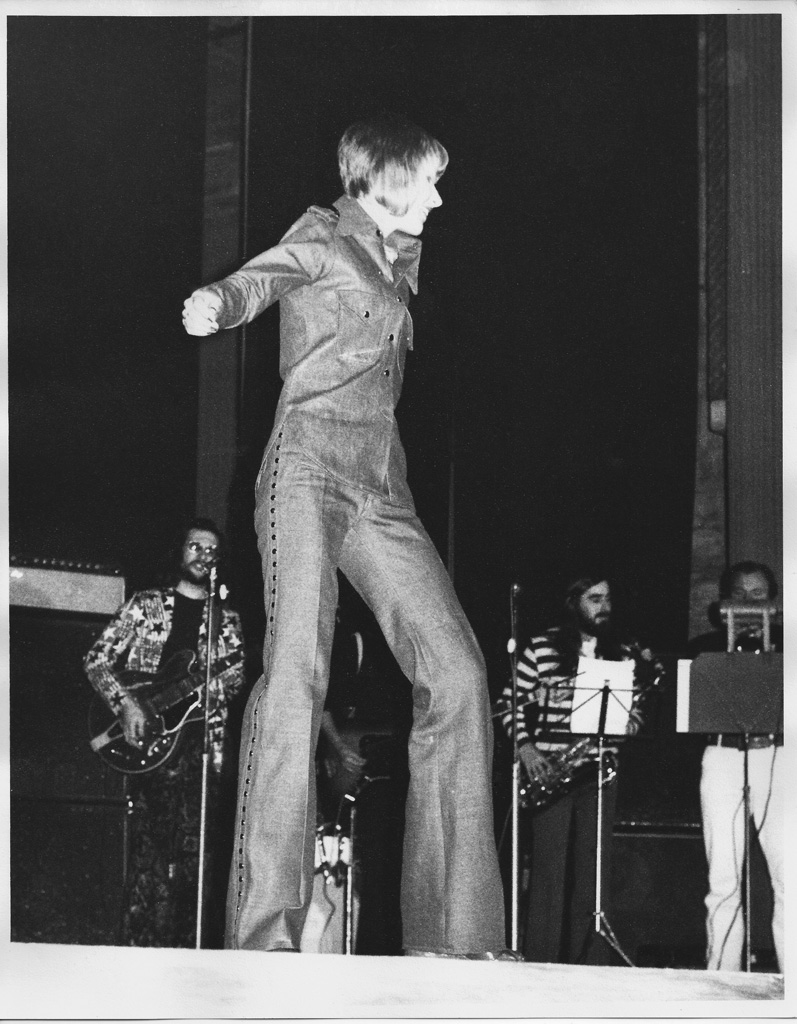

Ray Columbus’s signature look and dance move –entitled the ‘Mod nod’ – encapsulated the spirit of the time. Ray Columbus (left) on television. Television New Zealand Dunedin Photographic Collection, accessed https://bit.ly/3nMSWb1, CC BY-SA 2.0

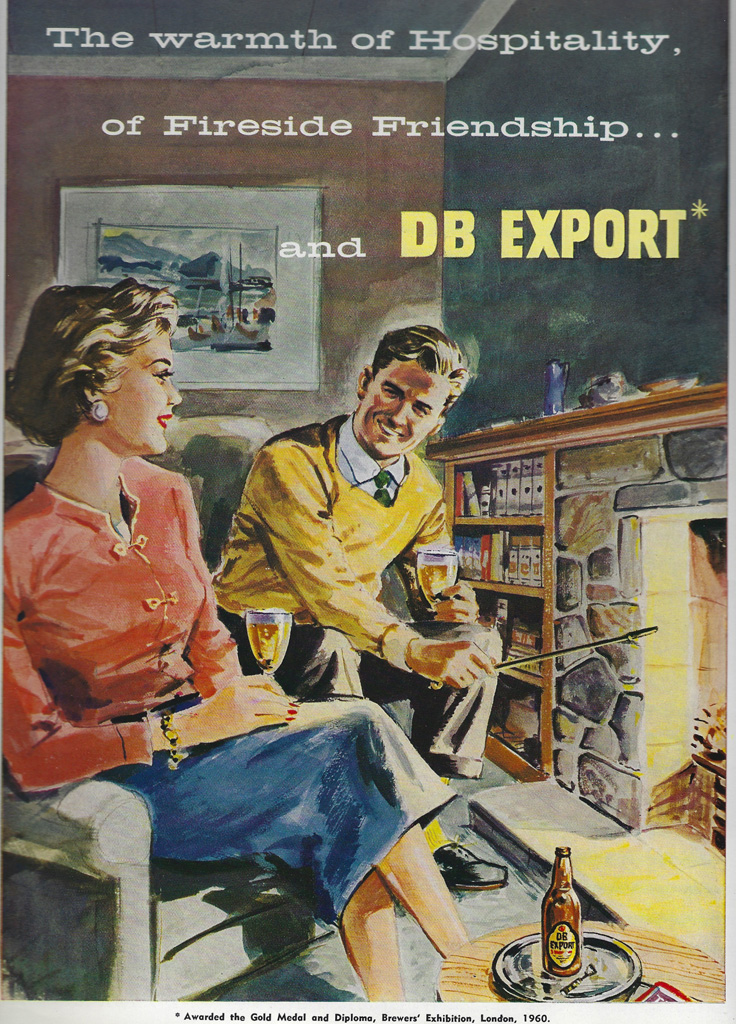

What did our world look like in 1964? The post-war restoration of the Western economy had progressed apace throughout the 1950s, and in New Zealand our standard of living ranked us among the top five countries in the world. On the back of our success as Britain’s farm – supplying meat, butter and wool – the country prospered economically, giving its citizens the wherewithal to embrace all that a bright new consumer society had to offer: a Keith Hay home in the suburbs with a Frigidaire refrigerator in the kitchen and a black-and-white television in the lounge. With such obvious prosperity, it is unsurprising that politically the country became more conservative and for 12 years from 1960 we had a National government led by ‘Kiwi’ Keith Holyoake, whose mantra was an uninspiring ‘steady does it’. Socially, there was little on offer beyond weekend sport, a night out at the movies, a dinner party at home, community gatherings such as socials and balls, for which everyone dressed up, and drinking, mostly beer.

Beer was the drink and this was our sophisticated version, which won the title ‘Best Beer in the World’ at the Brewers’ Exhibition in London, 1968. From The Mirror, March 1962

While the adult generations relished the rich new lifestyle that contrasted with their experiences of the preceding war and Depression years, their children had no such comparison – their normal was the freedom of a carefree life. The teenager was a by-product of this new economic and social order. They could stay at school beyond the legal leaving age and when they did enter the workforce there was plenty of paid work. With coin in their pockets, time on their hands and a boring buttoned-down society, this generation had everything they needed to create their own culture – one that would permeate every aspect of the activities they enjoyed: music, entertainment and fashion.

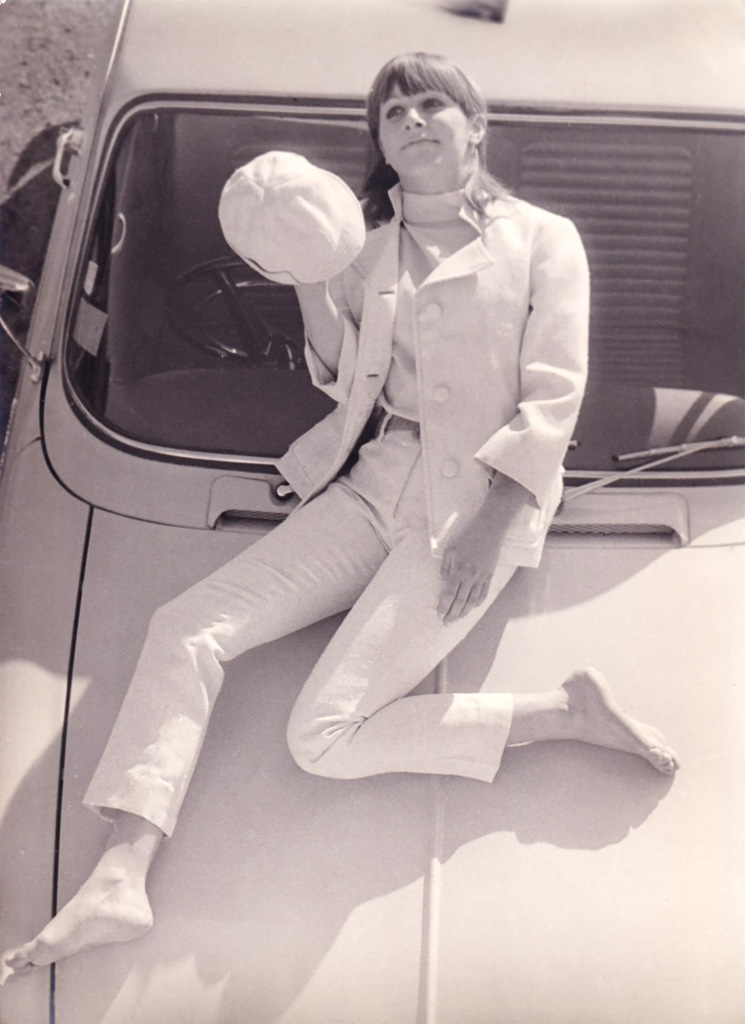

At this time, Western fashion, directed from the couture houses of Paris and London, was designed to flatter the mature figure with a bust, waist and hip, elegantly encased and embellished for sophisticated occasions. But the teen generation didn’t want to wear their mother’s clothes. Elegance and sophistication didn’t feature in the lexicon of youth – music, action and fun did, and their clothes needed to allow them to look the way they felt. The fashion photography of the day records this in the kooky and active stance of the models in the studio shots or outside, where they are seen on the move, running, walking or whizzing along on a moped.

‘The look’, as Mary Quant called it, had its origins in swinging London, but its echo spread far and wide – young women everywhere responded with their own version. Like Quant, Wendy Ganley started in a very hands-on manner, making her first garments herself and selling them through her own Elle boutique upstairs in Victoria Street, Hamilton. Creating what she and her friends wanted to wear, it took no time to develop an eager audience. One of her customers, Kathy Figgins, recalls having to make a quick decision and put her chosen dress on layby before it was snapped up by someone else.

The boutique environment, often small and on the margins, also expressed a youthful identity. Here designers created the world that they wanted to inhabit: quirky spaces with a relaxed informal atmosphere, loud pop music and hip, young sales staff. The synergy between music and fashion was a hallmark of the 1960s scene, with boutiques organising fashion parades in coffee lounges and bars, which were accompanied by live music performances. Far removed from the formality of the heavily scripted presentations that department stores organised, these were zany affairs more akin to a party than a parade.

Hamilton band, Mandrake, brought fun and excitement to this Elle fashion parade at the Founders Theatre. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Wendy Ganley

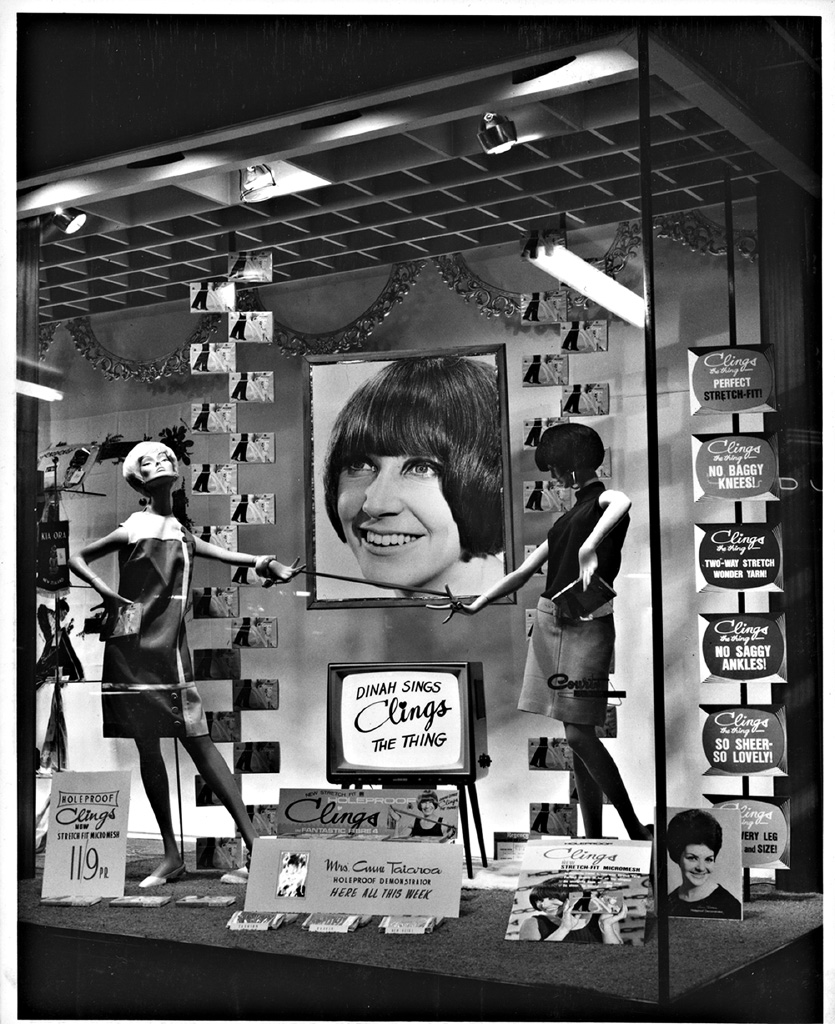

Pop stars like Dinah Lee, who released her first album in 1964 aged just 19, helped disseminate the new look. She became known here as the Queen of the Mods, dressing in clothes made by Diana Colemore-Williams of the Casual Shop, one of Auckland’s first boutiques, and her Vidal Sassoon-inspired hairstyle, which was cut by Jacky Holme, a cool young model and shop assistant who worked there. While Dinah Lee was not conventionally beautiful, her exuberance and the sense of fun in her performance perfectly captured the vibe of the time. In Britain, model Jean Shrimpton became the face of Yardley cosmetics; in Australia and New Zealand that face belonged to Dinah Lee.

Minis made legs the focus of attention. Dinah Lee became the voice of Holeproof ‘Clings’ in their television advertising and in this window at H & J Court department store on Hamilton’s Victoria Street. Image from the John Millar collection, Hamilton City Libraries – HCL_14607

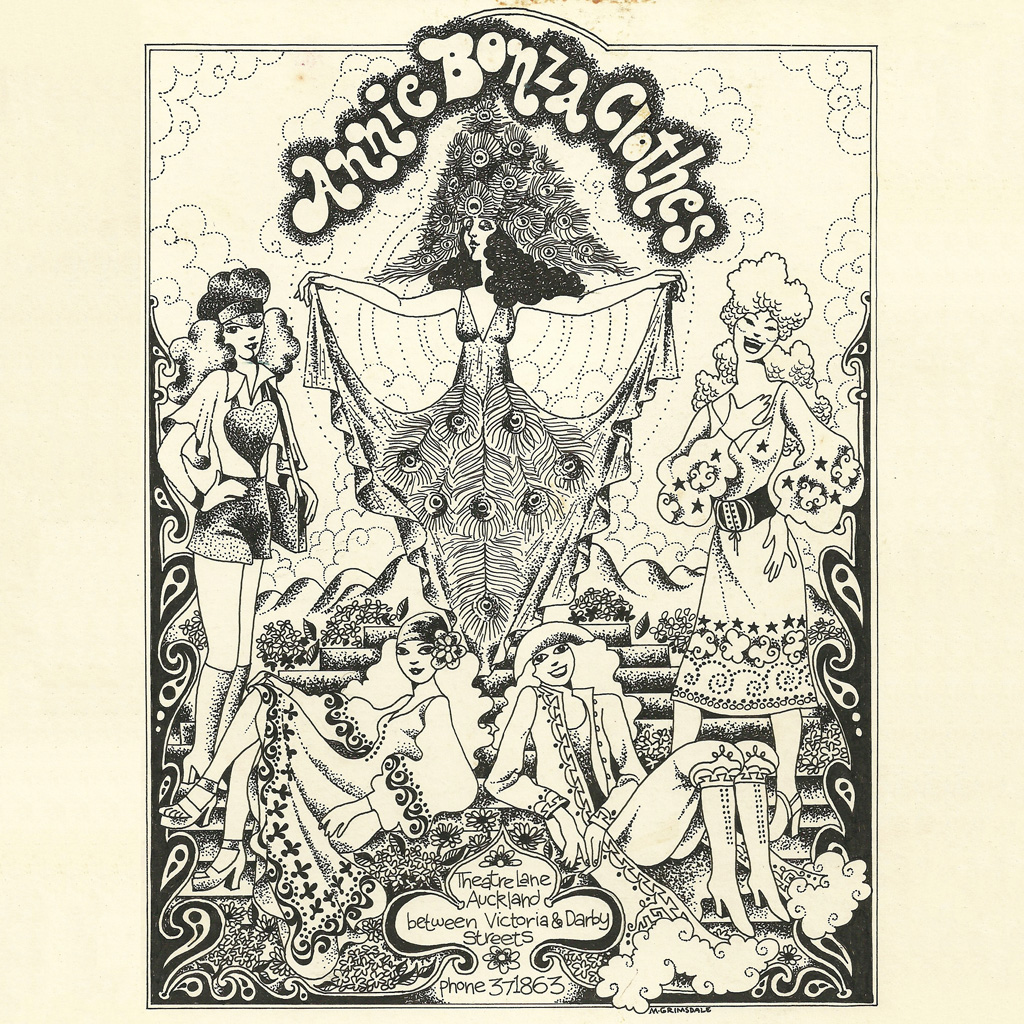

The mod look was as clean and sharp as a pop art piece by Billy Apple and in New Zealand the world of art and fashion was intertwined as it was in London. Designers like Gabrielle Sinton and Nicky Boyes, who established Bizarre in Victoria Street, Auckland, were graduates of Elam School of Fine Arts and the boutique’s swing-tags were designed by artist Pat Hanly. Dick Frizzell designed the signage for Nova in Theatre Lane and Ilam School of Fine Arts graduate Murray Grimsdale designed the Annie Bonza graphics. Boutique culture also drew its customers from the arts scene – artist Barbara Tuck was one of Elle’s earliest clients, and costume designer Enid Eiriksson chose to get married in a peacock blue Annie Bonza mini dress.

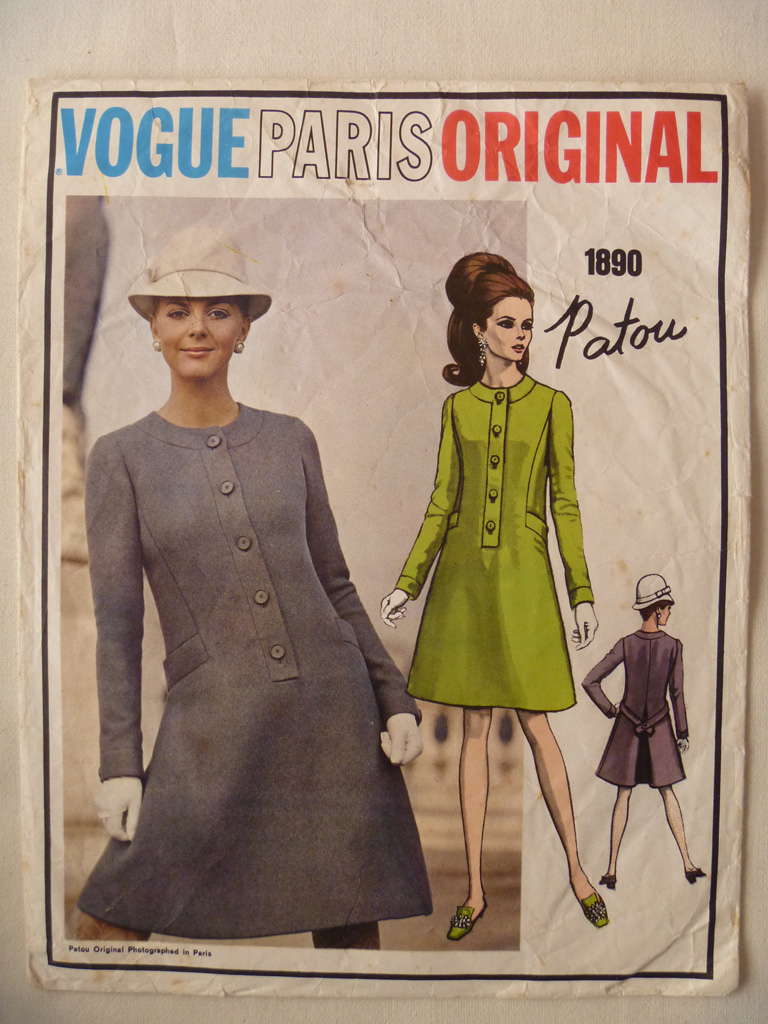

The decade also saw a shift of value in fashion. Work and play were accorded equal importance and the clothes you wore should allow for both, with no hierarchy of formality. Shapes such as the straight shift and A-line dress with hems finishing above the knee allowed for freedom of movement. The simplicity of the garment shapes meant that they could be produced for a moderate price, making their acquisition more democratic. Alternatively, they could be made at home. Sewing engaged a whole new following in this period: young women keen to have the newest fashions could make their own. For the cost of two yards of fabric and a few hours to ‘run up’ a frock on a Saturday morning, a young New Zealand woman could twist away the evening looking every inch the groovy miss, the equal of her London counterpart. Money saved on DIY dresses was available to be spent on such important style essentials as fancy tights, shoes and makeup. With bold colour and patterns more important than precise fit and finish, home sewing made the latest fashions achievable, affordable and readily available.

For the creative home sewer paper patterns made the latest styles easily available. Image courtesy of NZ Fashion Museum collection

In the 1960s, fashion-conscious New Zealanders remained focused on what was happening in the Northern Hemisphere and wanted to be up to date with the latest trends in music, fashion and lifestyle. With the advent of television, which made its first black-and-white broadcast at 7.30 pm on 1 June 1960, the wider world began its inexorable entry into every New Zealand home. The jet age arrived in 1965 courtesy of Air New Zealand’s DC-8 planes and the opening of the International Airport at Māngere in 1966. Together, this meant that our ability to see the world at first hand greatly improved, with travel to London now taking 36 hours and Sydney a mere four.

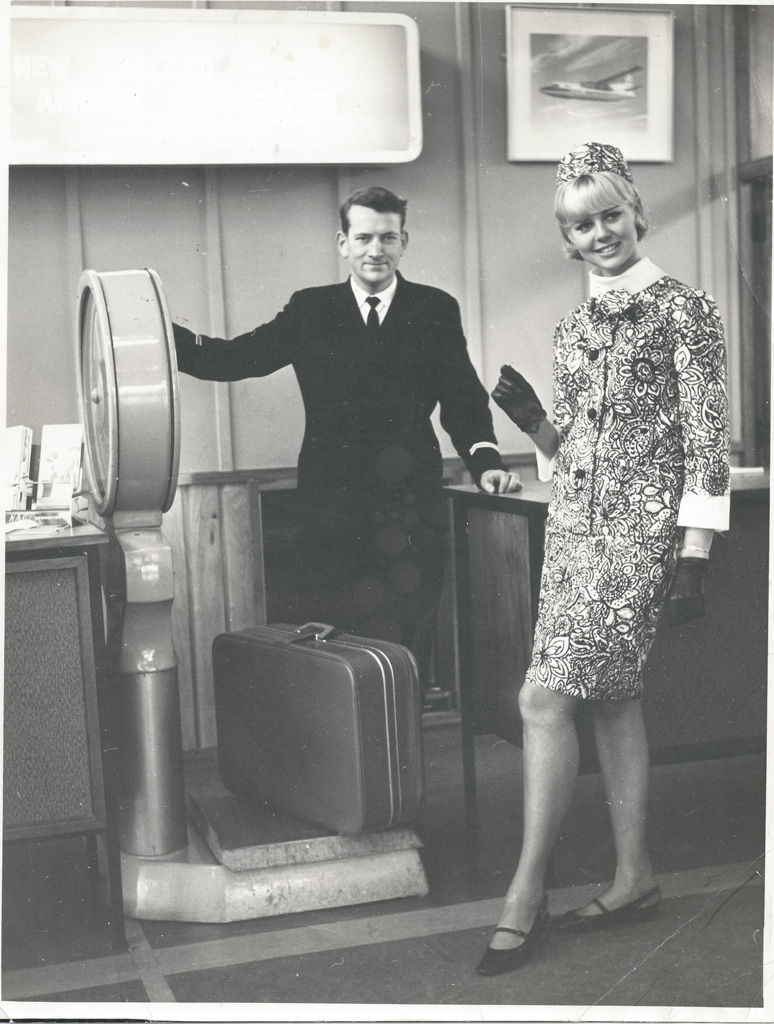

In 1965 NAC, our national carrier, advertised ‘Flying’s the way to travel’. This is how Elle thought it should be done in style. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Wendy Ganley

Youth fashion permeated the public consciousness on the main streets up and down the country, and on Saturday night, with only one television channel, pop stars like the Chicks and energetic go-go dancers, all dressed in brightly coloured mini dresses by Annie Bonza, were beamed into the nation’s lounges on music shows like C’mon, New Zealand’s answer to the United Kingdom’s Ready, Steady, Go!. When, in 1966, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, widow of the assassinated President John F Kennedy and a style icon, wore a thigh-high skirt for the first time in public, the New York Times declared that the future of the mini was now safe. ‘The look’, pioneered by Mary Quant, had become ubiquitous and was being worn by all ages. It was the first time that a fashion did not originate from the prevailing conventions of couture but instead had its origins in youth culture on the street.