The majority of the 76 photographs in Max Oettli: Visible Evidence, Photographs 1965–1975 were taken at night, and most are of Auckland. The subject is not so much an unseen city, but one more closely observed and caught unawares. A midnight rambler armed with a Leica, Max Oettli made it his mission to record Aucklanders in their natural habitat.

The period covered in the exhibition, 1965–1975, roughly corresponds to Oettli’s employment as photographic technician at the Elam School of Fine Arts. After hours, when not making the most of the school’s darkroom, his ‘night beat’ covered Auckland and the inner-city suburbs, and occasionally further afield. As if to heighten the mystery of many of these images, titles tend to be fairly general: in the case of most of the night shots, only the time (eg 2am, 5am, after 10pm) and the year are given. It seems appropriate that an introductory panel in this exhibition includes a self-portrait of the photographer presenting himself in penumbra, with half his face in shadow and his ever-present camera slung over his shoulder.

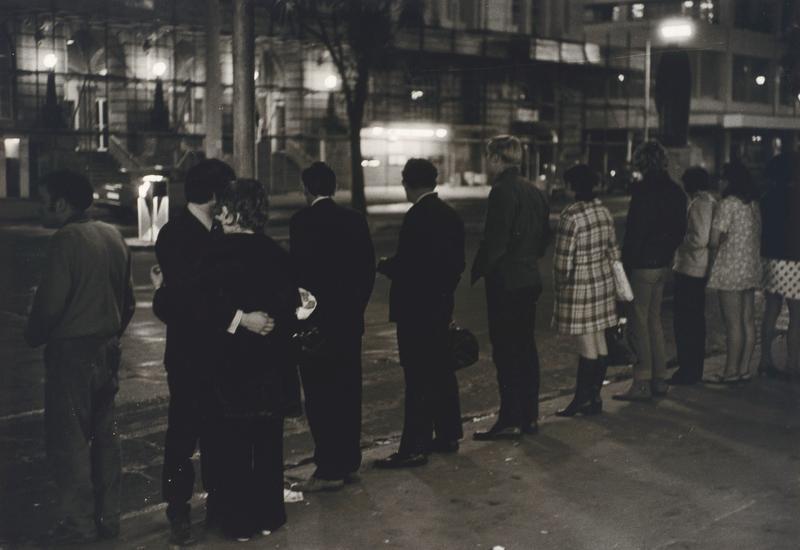

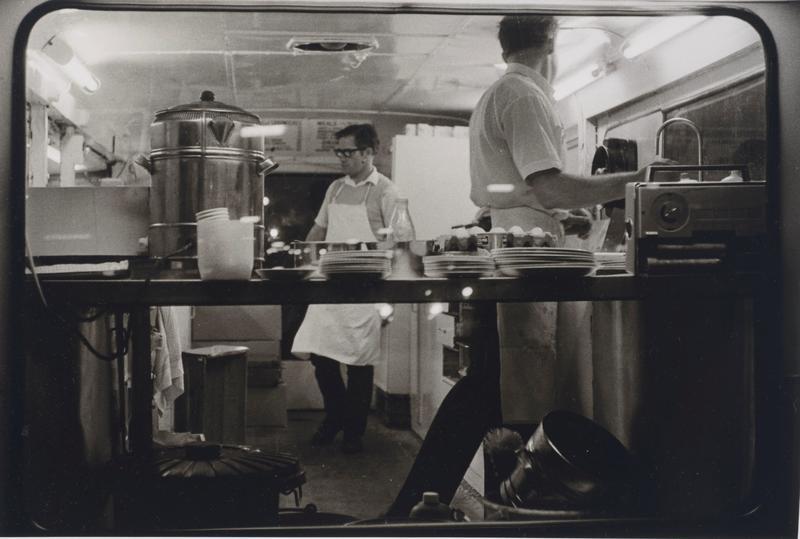

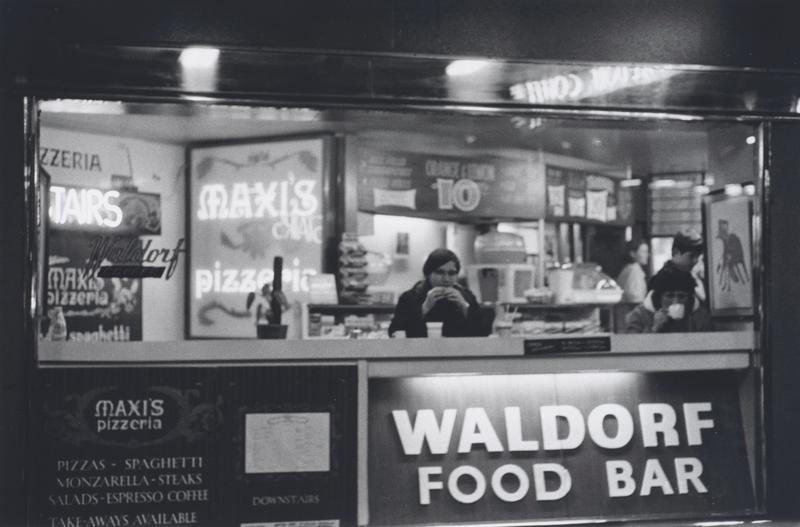

Oettli has described his technique of ‘sidling’ up to unsuspecting subjects who for the most part are unidentified. They are oblivious to the approaching photographer, as is apparent as in the line-up of 11 patiently waiting individuals in Bus Queue, After 10pm, 1971. People were the primary subjects, furtively secured on film during fleeting moments, but many of their after-hours haunts would also prove transitory. Oettli’s photographs offer glimpses into once-thriving public institutions that, half a century later, are no longer with us: the patrons of the Hotel Kiwi (later known as the Kiwi Tavern) at the top of Wellesley Street, the White Lady pie cart parked in Shortland Street, and the Waldorf Food Bar in Queen Street are now, half a century later, non-existent.

Richard Wolfe

Article Detail

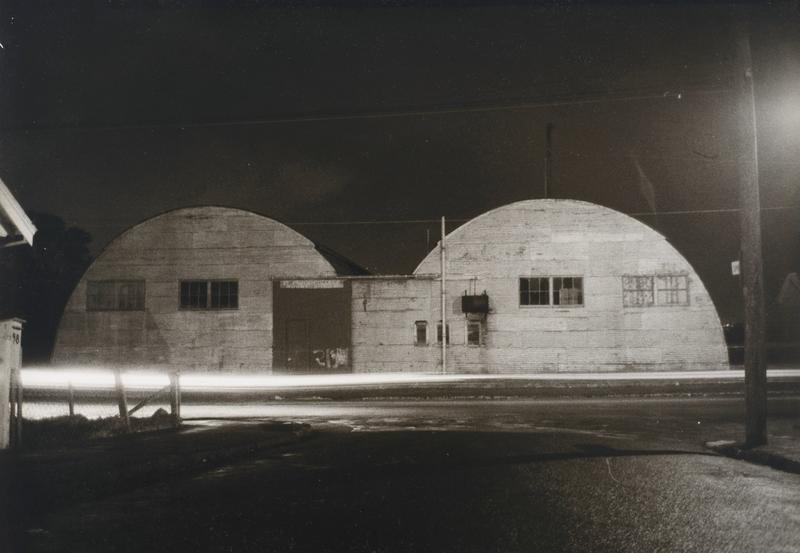

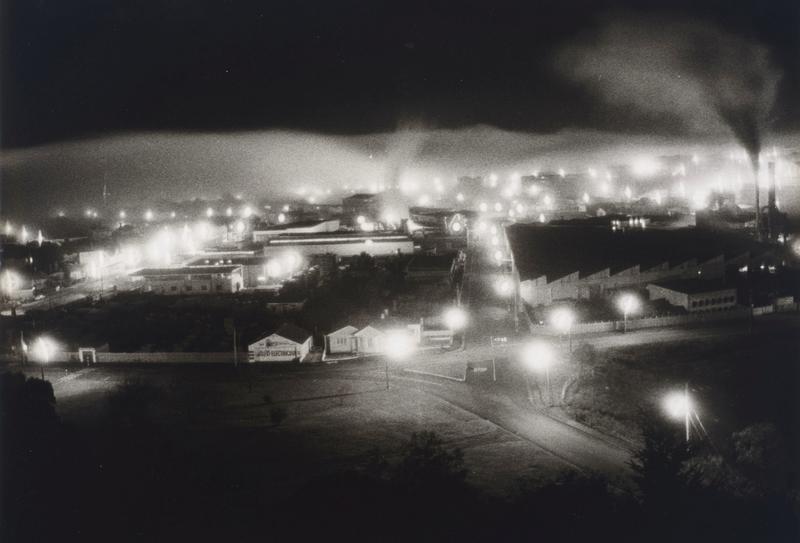

As seen in this exhibition, Oettli largely eschewed the landscape for the built environment, and for selected architectural statements, now also gone. They include the pair of igloo-like structures that were once rugby training sheds at St Paul’s School, Ponsonby, and the two tall cylindrical towers that distinguished the Tip Top bread factory in Kingsland. The dramatic and panoramic night shot of Henderson and Pollard’s timber yard in Mt Eden is another record of a part of Auckland that no longer exists, a victim of urban renewal.

Subjected to Oettli’s imaginative and roving eye, everyday buildings can assume other evocative, uncanny dimensions, evoking a sense of loneliness and melancholy. The available street lighting in Helensville, 4am, 1972 makes old wooden business premises resemble a Wild West film set, while its appropriately weather-beaten ‘Verona Panel Beaters’ sign contributes to the general air of mystery and impermanence. And in Night Parnell, 1972, a curtain billowing from an open bedroom window of an otherwise unprepossessing wooden house may echo breathing of a sleeper within.

In many instances Oettli was looking in, as through the window of the Fadex skincare shop near the front entrance of St Kevin’s Arcade with its unsettling display of organic creams and soaps for such afflictions as dandruff, varicose ulcers and eczema. On other occasions the photographer was on the inside looking out, observing those on the outside looking in. In West Wind Coffee Bar, 1968, a diner returns the gaze of the passers-by, and Oettli was on hand to capture the visual interaction between the two parties. Commercial premises proved a fertile source of imagery; in Models, Shopwindow, Queen Street, 1971, a shop assistant adjusts a mannequin, uncannily looking like one herself.

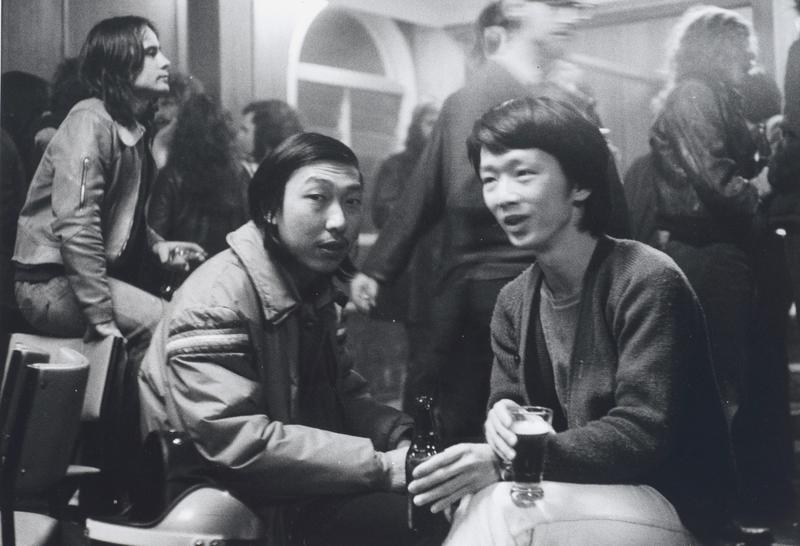

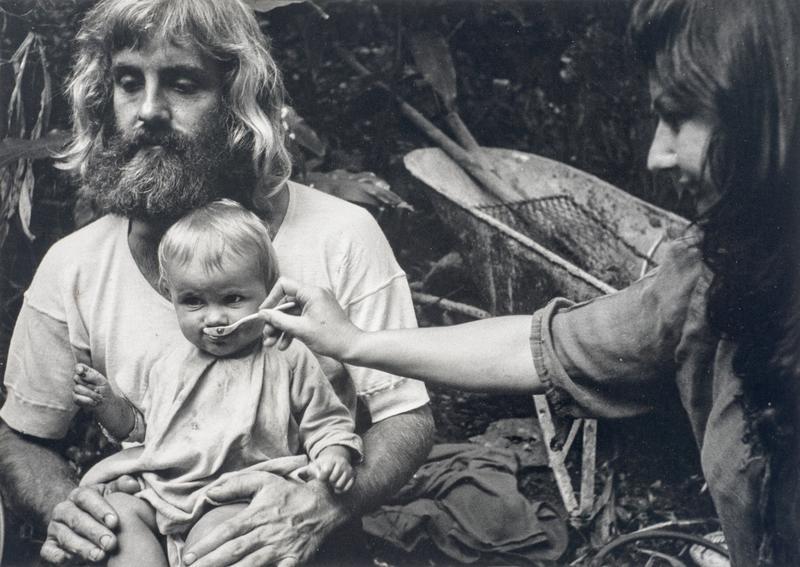

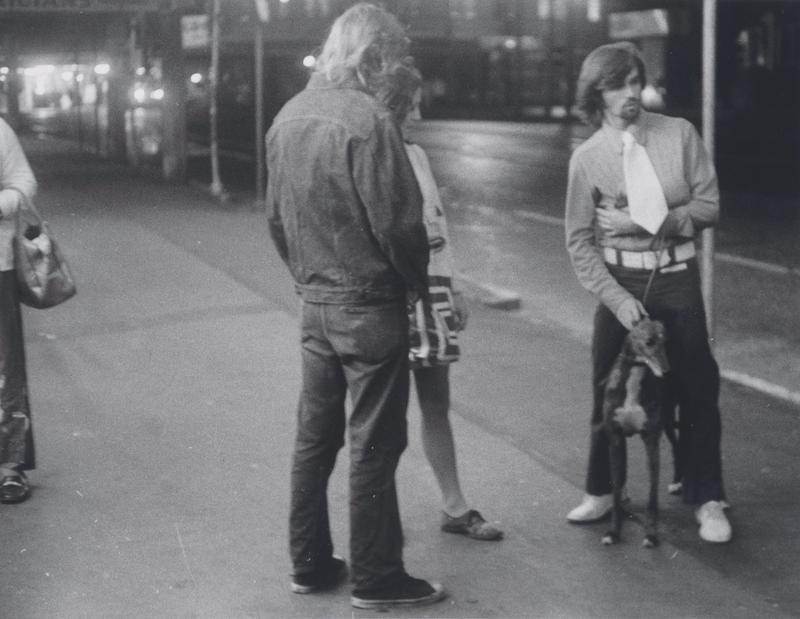

While many of these images are of a universal nature, being records of everyday (as it were) activities, some also evoke the spirit of the times. In an intimate family portrait taken in 1973, the memorably named Stonewall Jackson and his young son exhibit clothing and hair styles that typified that decade. And so it is with another pair of individuals spotted In Karangahape Road in 1971: a male decked out in double denim converses with a dedicated follower of fashion whose main sartorial statement is an extremely wide tie.

Venturing into the art world, a lone visitor, expressing bafflement – and/or perhaps disgust – is caught in the act of engaging with the Marcel Duchamp exhibition at the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1967. Most of Oettli’s subjects are equally anonymous, apart from a number of insightful portraits of artists, including Phillip Dadson, Gretchen Albrecht and Marté Szirmay, as well as cultural historian Eric H McCormick. In contrast to these single shots is a remarkable series of eight photographs of an increasingly concerned Rodney Fumpston, submitting himself to fellow students at the Elam School of Fine Arts. He is recorded being systematically entombed in wet plaster, in a rare demonstration of the otherwise lost art of life casting.

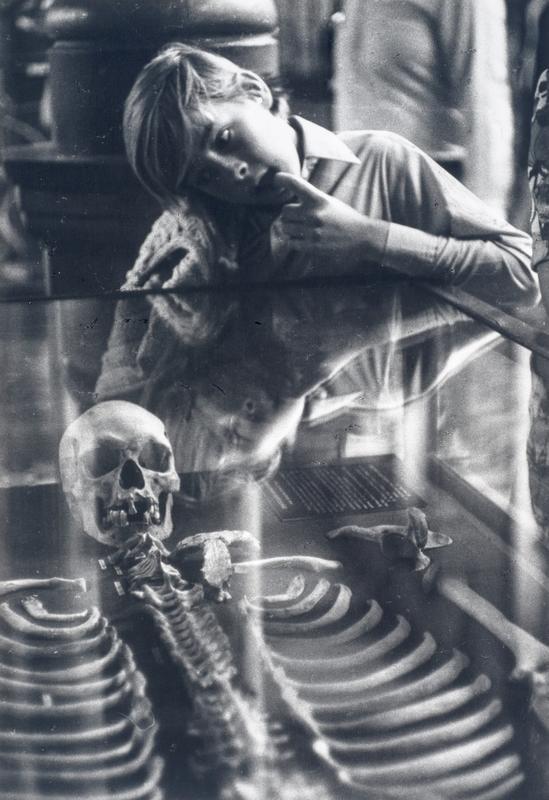

Thanks to their previous appearance in publications, some of these images may be familiar to some viewers. One such is Leonard and Rover, 1974, in which the former sits comfortably reading in a nightshirt (also very fashionable in the 1970s), while his canine companion adopts an unusual pose up against the door. In the same category, Girl Licking Escalator, 1971, is a delightful study of a child lost in the moment, unwittingly exposing herself to the grime of the city. In a similar vein, in Boy and Skeleton, The Australian Museum, Sydney, 1972, Oettli captures his young subject lost in the contemplation of mortality.

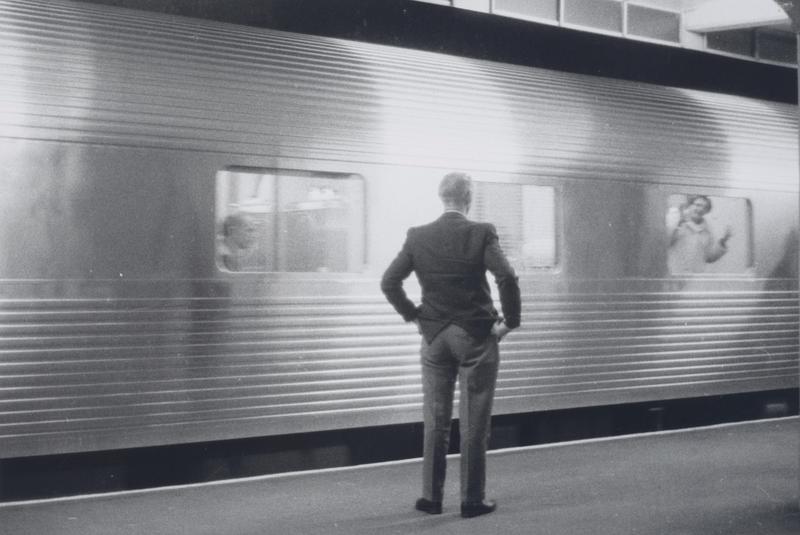

While keeping his physical distance, Oettli manages to insinuate himself into situations. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the unfolding human drama that is Silver Star (2), 1973. A man, standing alone on a railway platform and farewelling a female passenger, is unknowingly observed by another, thereby producing a three-way interaction. And typical of Oettli’s observations, it all takes place through the windows of the train.

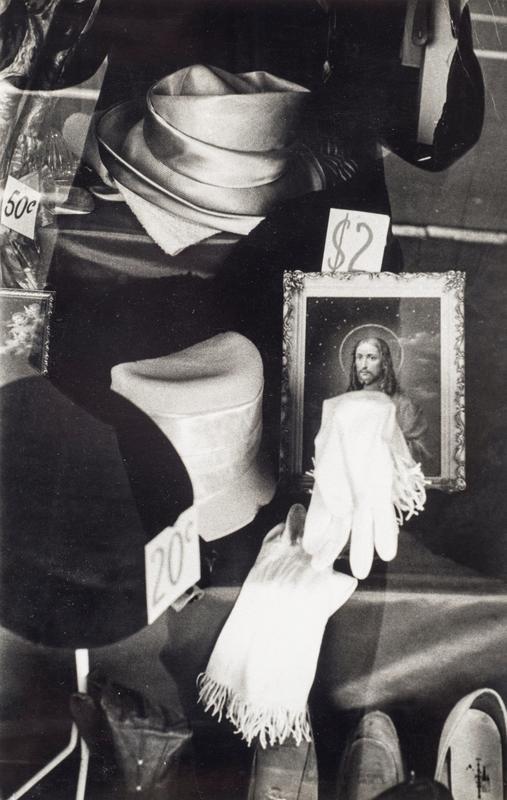

Wry humour is apparent in the thrift shop bargains recorded in $2 Jesus Ponsonby, 1970. And in the same part of town, in Fish Shop (3), Ponsonby,1967, the stance adopted by a small boy mirrors a figure in a painted mural, while the photographer – caught between them – captures the passing resemblance in this unlikely conjunction.

A more serious side of Auckland is apparent in a study of graffiti, Yes No, 1971, implying disagreement or perhaps ambivalence over some unspecified issue. Mixed emotions are seen on the faces of the crowds at a 1972 anti-Vietnam War demonstration, and at the return of soldiers from that controversial conflict the following year. A similar theme is suggested by one of the few still life images, Napoleon and Anzac, 1971. In this domestic interior a large framed print of heroic action during the Napoleonic Wars is thematically linked to a family photograph of a First World War New Zealand soldier in his distinctive lemon-squeezer.

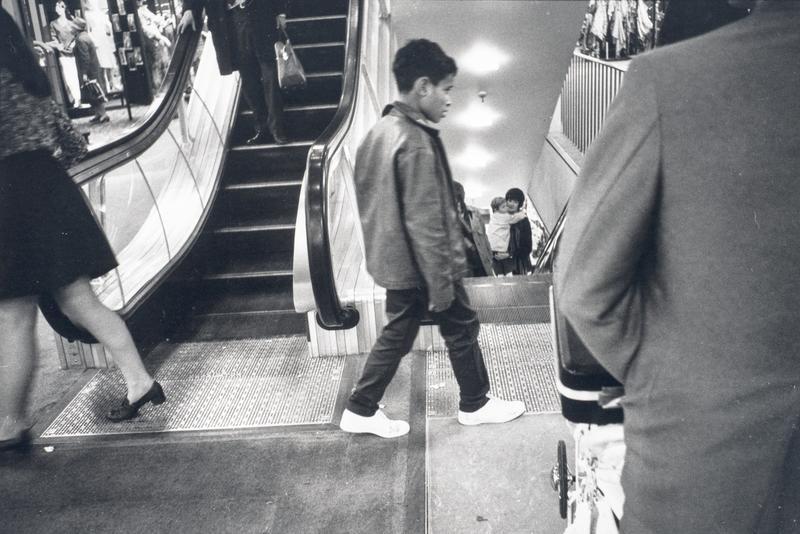

In almost all cases Oettli’s subjects are static, as if transfixed by his approaching camera. A rare exception is the record of human activity that is 246 Department Store, 1973, a complex composition in which escalators are ascending and descending, and shoppers are variously entering and exiting the frame.

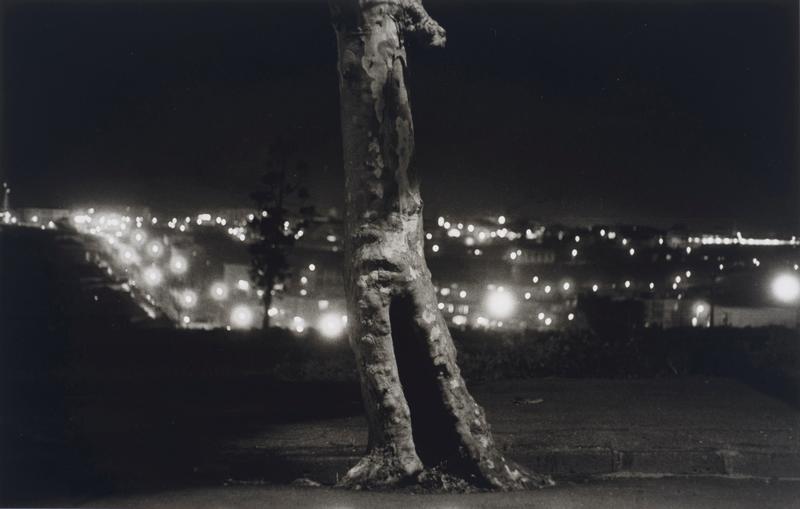

While most of these photographs are distinguished by a human presence, Oettli was also able to seek out nature’s anthropomorphism. Thus the suggestion of human likeness by a tree in Freemans Bay, 2am,1971 is dramatically enhanced by the darkness. Similar nocturnal atmospherics are evident both in Domain, 3am, 1971, in which a clump of trees is spookily illuminated by a pair of streetlights, and in the eeriness of the vehicle-free motorway underpass beneath Symonds Street in Night Out, 5am Grafton, 1972.

Charles Dickens may have provided a historical precedent for Oettli’s after-hours activity; when suffering from a bout of insomnia he walked the streets of London, encountering scenes of homelessness and social deprivation that provided raw material for his books. Oettli’s eye was likewise drawn to the idiosyncratic and the otherwise unnoticed – and undocumented – in what amounts to a wide-ranging and largely affectionate record of fellow citizens in their – and his – urban environment. He has acknowledged that the greatest single influence on his own development as a photographer was the catalogue of the 1947 Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The exquisite gravure reproductions in that publication demonstrated how a photographer with a ‘hidden eye’ could operate effectively while being out of both sight and reach of his/her subjects. By such means, Oettli encourages us to reconsider the overlooked and the under-appreciated. Unaware they were being recorded for posterity, his unconsciously cooperative subjects became players in this highly personal and engaging perspective of one decade in our collective social history.

-------------------------------------

Richard Wolfe is a freelance writer, and author and co-author of some 40 books. He has a BFA from the Elam School of Fine Arts (1969-72, when he coincided with Max Oettli) and a PhD in Art History from the University of Auckland.