Tuesday 31 December 2013

Ron Brownson

For more than three decades Mark Adams has followed a singular direction in his art. History is always present as is the presence of people. This does not mean that one sees images of people posing in his photographs. In fact, he rarely includes humans but their lives are always there in spades. As is Mark's view of colonial New Zealand history.

"History" painting is rare in New Zealand and always has been. Not so with photography which always has history inserted into its own reality, even if it is consciously avoided. What Mark does is capture history as a visual tracery of the past. He travels to places that have substantive human history.

Very many places have such a significant history for our culture's reality. There's an old trope used about New Zealand that critiques its newness as a country appearing to have a short past. Such as believing there's no history here. Just look around, we may not recognise our visual archaeology of place but it is forever present.

To an extent, looking at a Mark Adams photograph is to look at oneself looking at the past. What can we recognise and what do we recognise? This proactivity, of expecting us to see more than surfaces is everywhere in Mark's art. Not only does it look at history, it comments on how we look at history.

These two photographs complicate this issue of where time sits even more, they are looking at another artist looking, but in the past. In this case it is the art of the Reverend Dr John Kinder. These two images are included in Kinder's Presence, which is currently on show.

Mark has gone to two sites that Kinder himself made famous through his watercolours of the same location painted over more than a century ago.

In his photograph Outlet of Lake Rotokakahi, Mark turns his back on the view which Kinder made of Rotokakahi. 1866. Outlet of Lake 1866 and looks back from what the painter would have been recording when he visited the Thermal regions in the mid 1860s.

What we see in Mark's shot is the road's path into the view that Kinder was making. In his image Te Wairoa, The Buried Village, he carefully attempts to replicate the place that John Kinder stood at to make his watercolour view The Wairoa near Lake Tarawera with Mission Chapel of Te Mu January 4 1866 circa 1886. At left is the stone pataka for storing food.

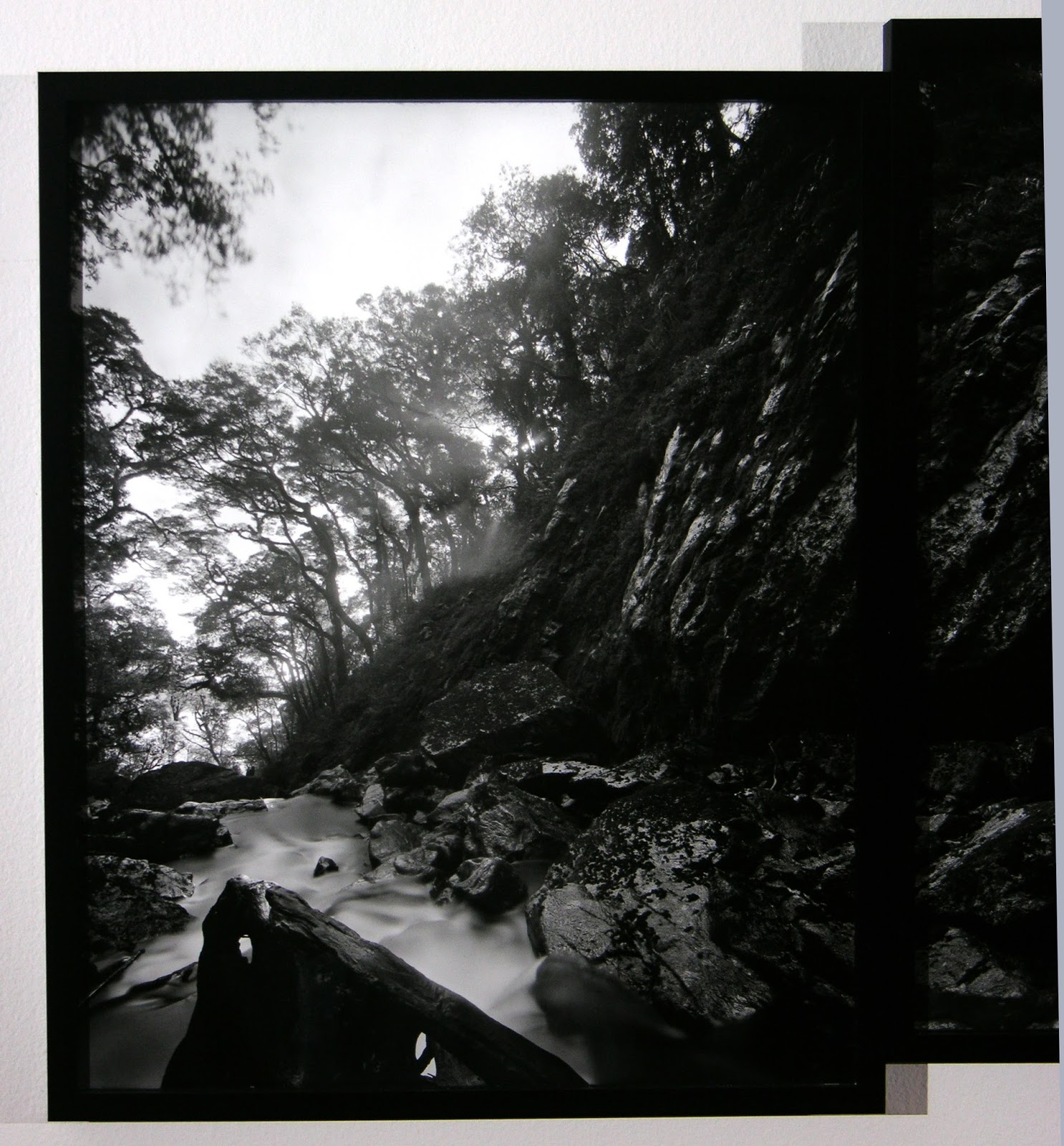

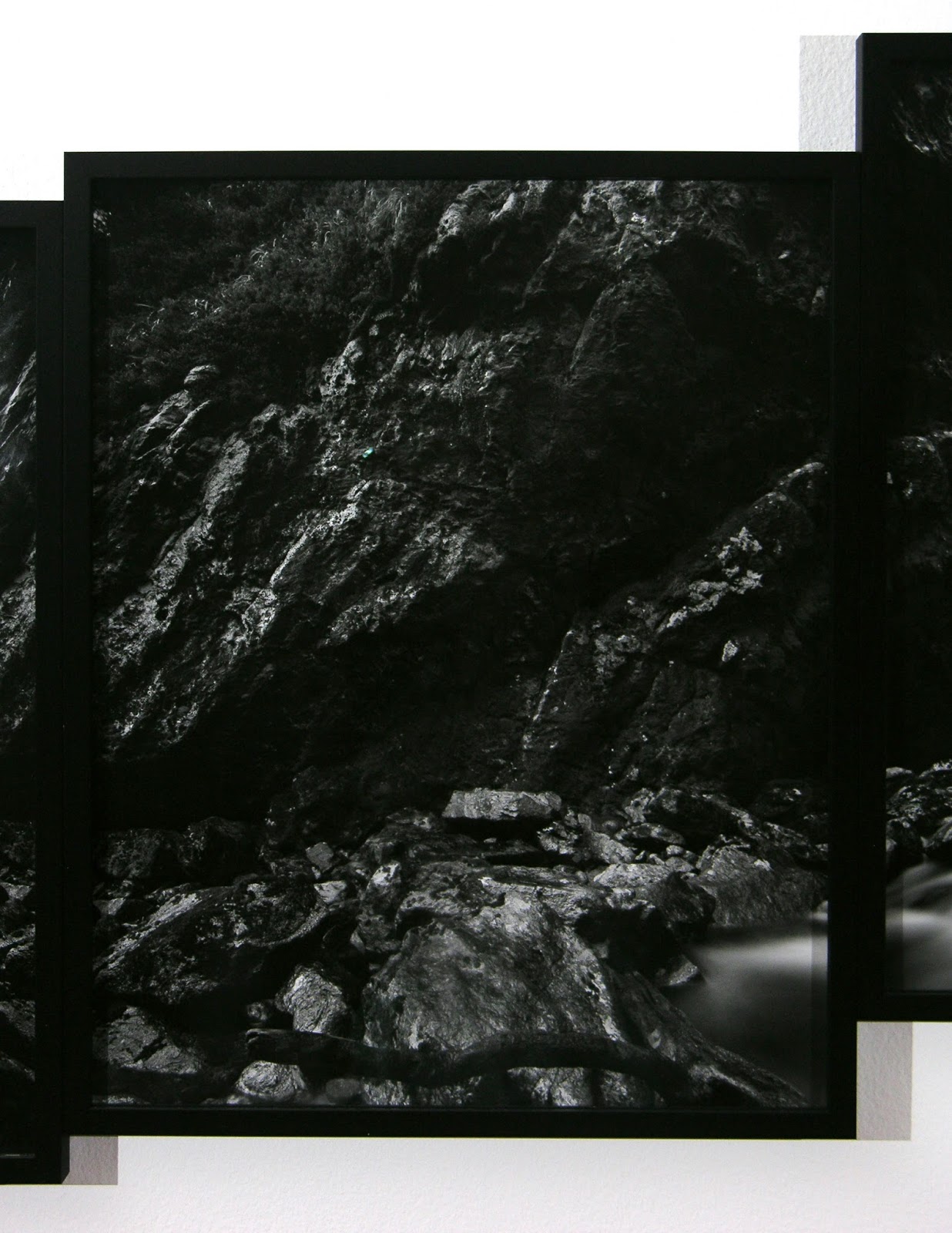

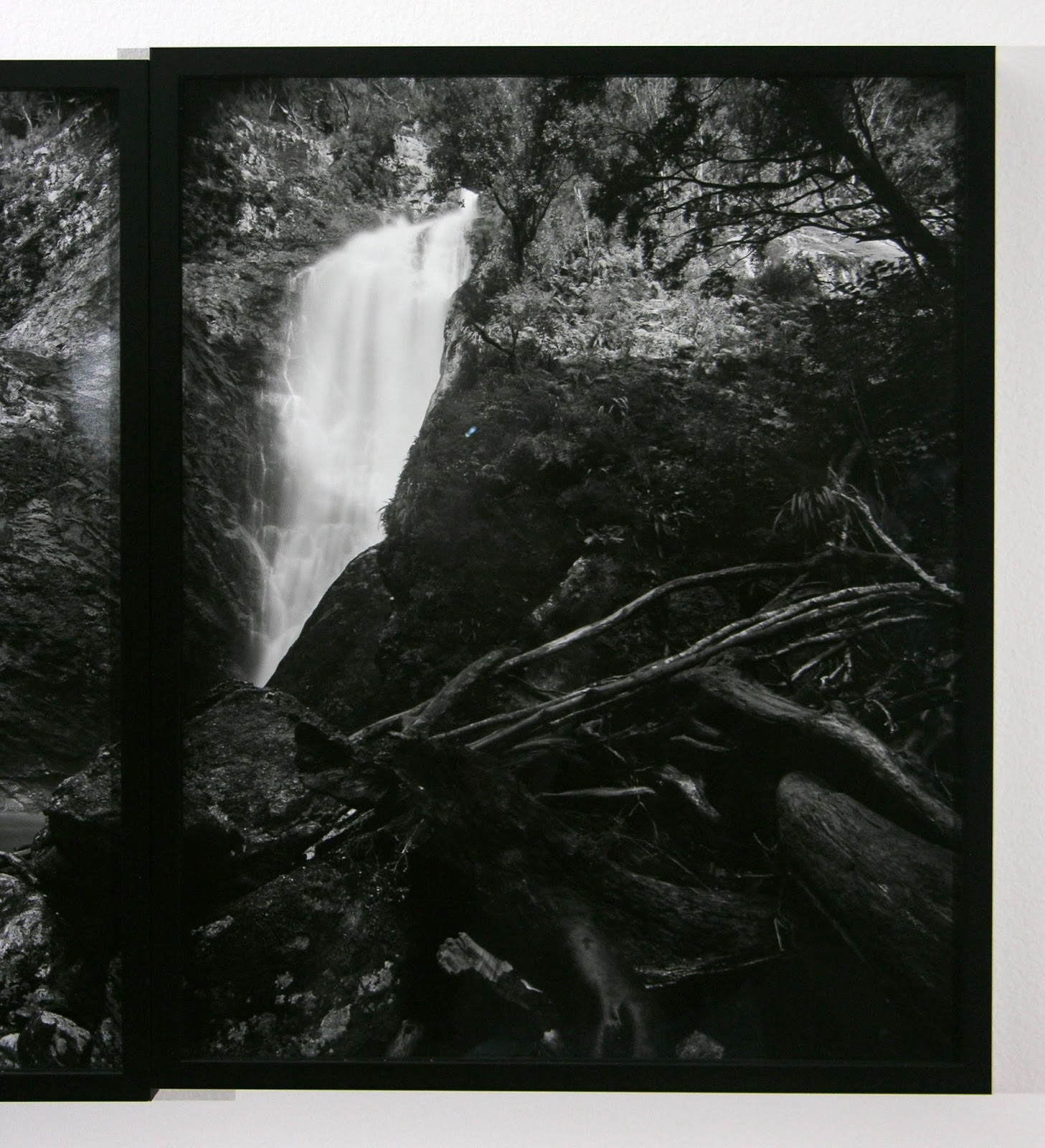

In Mark's multi-part panoramas the company of time is even more obvious. In After William Hodges' 'Cascade Cove', 21 May 1995 2005 he commemorates the visit of Lt Pickersgill with three companions to the waterfall at Cascade Cove in Dusky Sound on 23 April 1773.

Made famous by William Hodges's painted view of the same waterfall, this place is one of the few sites that one could now visit and see it essentially the same as it looked to Cook's men. How many other of 'Cook's Sites' are still able to be seen as they were? Oddly, there are very few photographs of this actual location available on-line, one has to visit it to get a true sense of its sublime qualities; the very same awe-inspiring feeling that caught Hodges's imagination.

Yet, when one surveys the four parts of Mark's panorama you see how difficult this photograph was to make with large format photographic equipment. It would be a challenging task at any time, let alone in the middle of the winter of 2005. To move from one image to another requires the camera to be adjusted with planned acuity, which is why the panorama has to be fitted together like image building-blocks.