RB: When you left art school, your teacher Anthony Caro said to you: ‘I hope very much that you won’t succeed, but I rather think you might.’ Did that comment act as motivation?

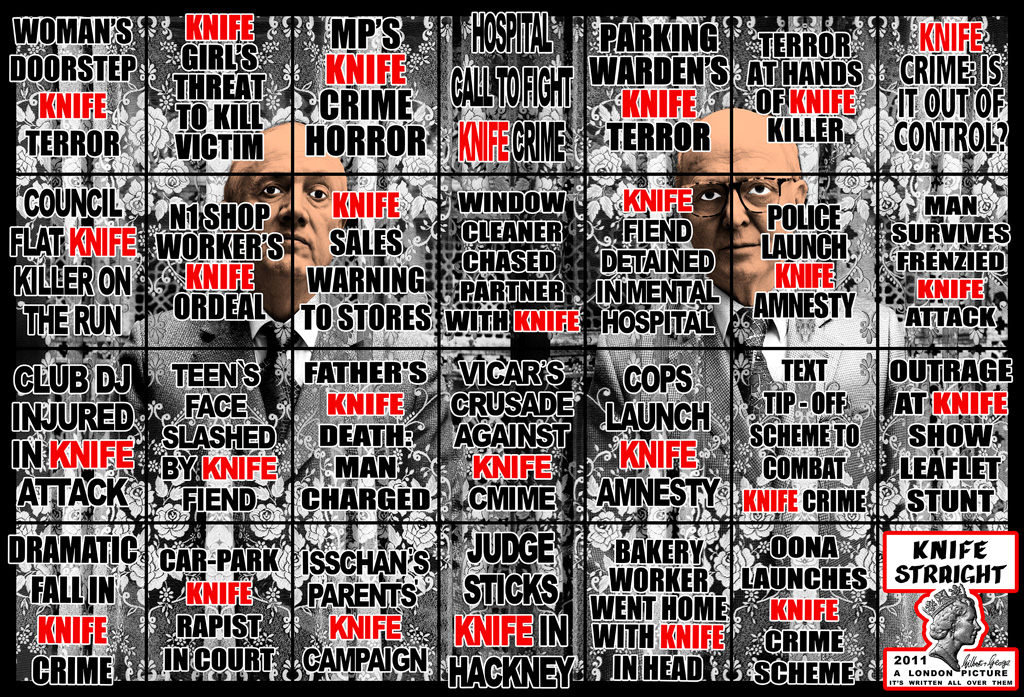

G&G: That’s exactly what he said. I think it’s very simple. We were part of St Martin’s School of Art, where sculpture was the activity: shape, form, colour, angle, corners – it had no human content. If you took the sculptures away from the college and put them down in Charing Cross Road, no one would notice them. They wouldn’t mean anything. We wanted to create artworks which had a human sense, that had a purpose. That can form life, form tomorrows, that can speak to sex, money, life, fear, crime, death. Not art about art, not formalistic art about shapes. We never wanted shapes, we only wanted humanity in front of us.

RB: Am I right in thinking that there is no biography about Gilbert & George?

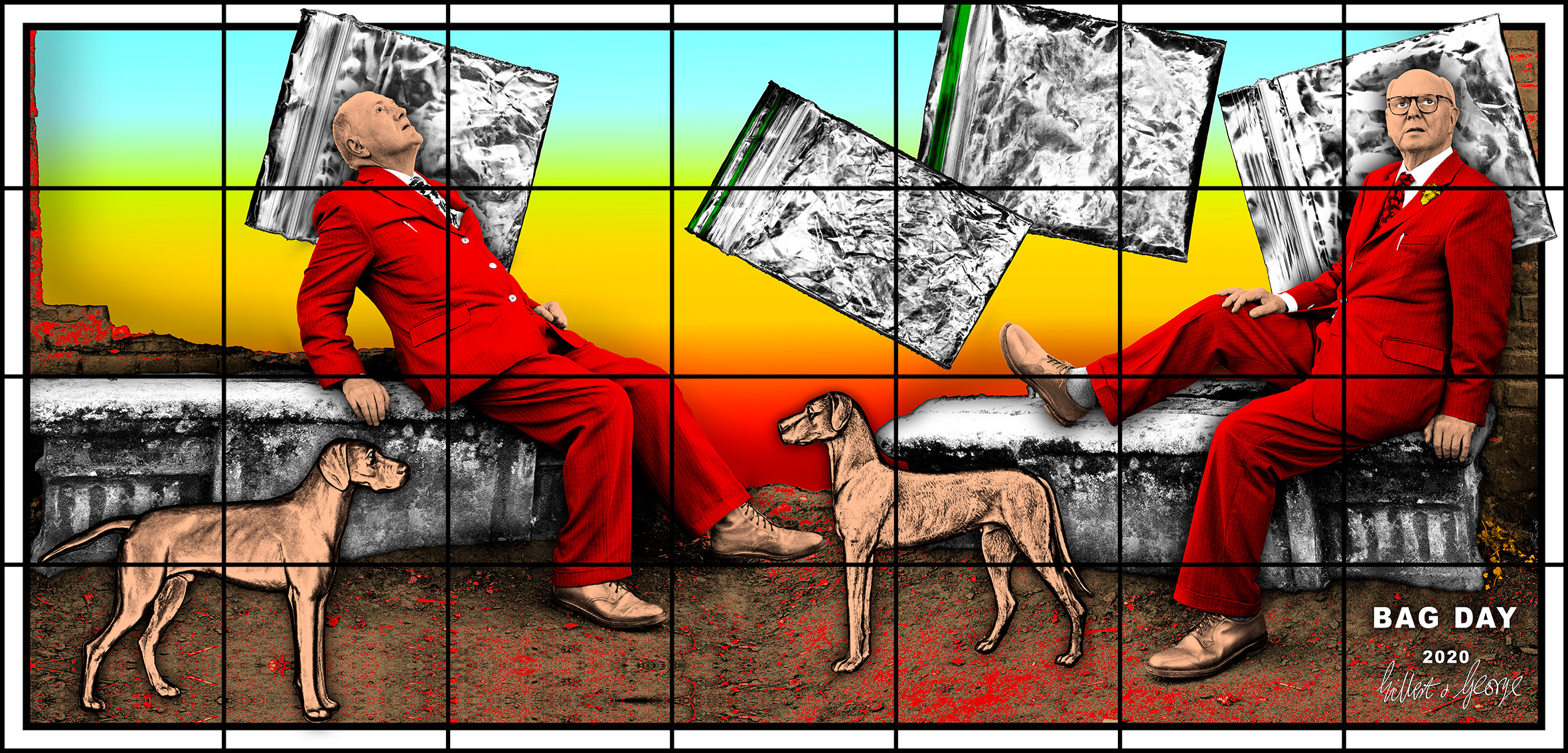

G&G: No, not yet. But in fact all our life is our pictures – our pictures are our life. We have made 5000 pictures and we are telling the world what we feel, what we believe, what we see, what we regard as good, what we regard as bad. So, all this emotion, this morality is the art. And we are in the centre of it, we are the object, the living Buddhas or whatever you call it.

RB: Aren’t all the pictures in a unique edition?

G&G: Yes, one-offs, because it is very elaborate to make them. It’s not easy. The making of it is quite complicated.

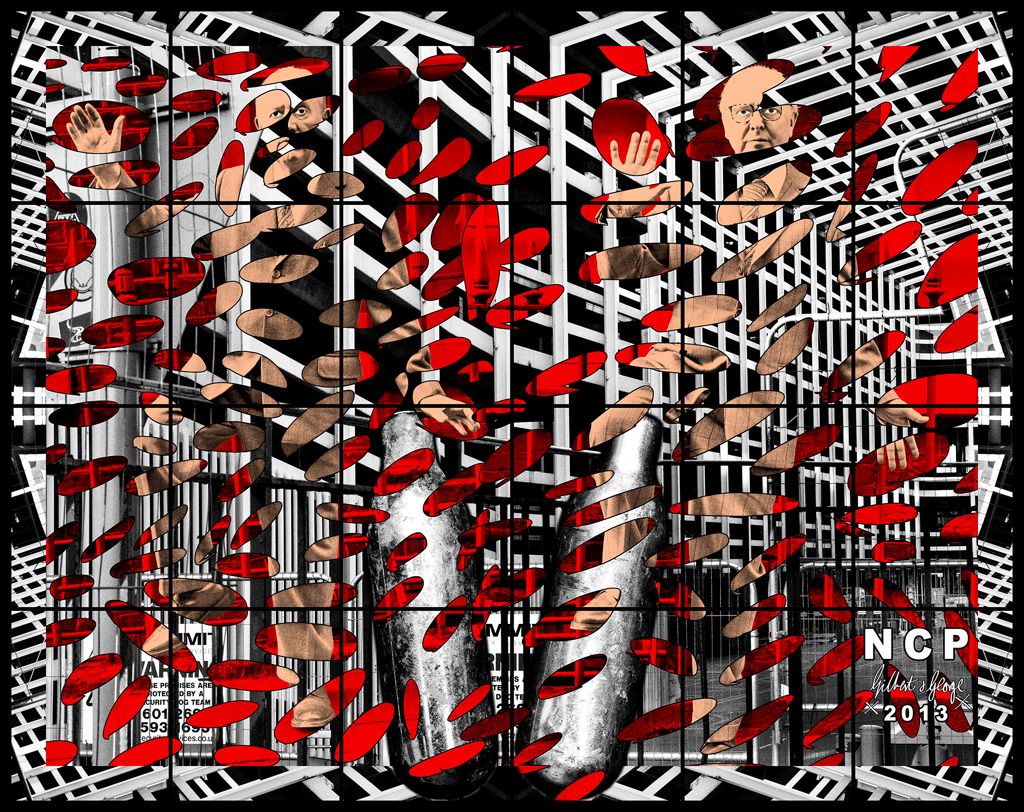

RB: For a period you were using an analogue technique of image generation, which was in the old photographic terms, the thing of negatives, transparencies, prints, dark rooms et cetera. But from the 21st century everything has been digital, is that correct?

G&G: Yes, we changed over to digital about 20 years ago. For us it was fantastic, because although it took us a while to learn how to work digitally, everything is now open to us. It’s extraordinary. We can be octogenarian and still do it. We don’t miss the darkrooms – all those trays and the smelly things and the red bulbs. The only things we miss are the rubber gloves.

RB: Were they full-length rubber gloves, up to the upper arms?

G&G: Steady now.

RB: Chemicals can burn the skin. We know that here in New Zealand because we have so much farming. Farmers often wear gloves.

G&G: I thought one used gloves in sexual games.

RB: I don’t think that’s what’s happening down on the farms. I’m not exactly qualified to comment . . . You first met in 1967, is that right?

G&G: Yes, Swinging London, we thought we were at the centre of the universe. Free love. We both come from backgrounds where we were baby artists even before we met. We had an interest and experience in figuration and thought and feeling, of hope and dread, and then we came together and made a union.