Lowering cost, improving the efficiency of creative outputs and making art easier to make (especially for those new to it) seem to be the main appeals of AI art. However, AI-generated art would not exist without pre-existing, man-made artworks. This is incredibly disrespectful to artists around the world, as art is not cheap precisely because of the time, resources and skill that an artist needs to hone before they can sell their work.

Some might argue that AI art will be similar to photography. It won’t wipe out painting or drawing, but instead will be its own medium. This thinking, however, is flawed. Compared to photography, AI is fundamentally different. Photography creates an original piece of media as both a tool for the visual arts (for example a reference tool, recording ephemeral art, etc.) and as its own medium. Over time, photography proved itself not to be a threat to the existence of other visual arts, but instead as its own separate artform. AI, however, cannot be considered its own medium because of all the issues regarding copyright infringement as well as the fact that it can’t exist independently. It will always reply on data from images and art made by other artists for it to be able to create ‘original’ works, which just makes it counterproductive. Moreover, AI art raises ethical concerns regarding how fast it can generate outputs from written prompts. Anyone can use AI to produce art that could defame another person or be harmful to human rights. If these issues are resolved in the future, then there may be a chance for AI to be used as a tool for art creation – helping artists gather inspiration or ideas – although not so much as a standalone medium.

In addition, AI art or generative AI in general also negatively impacts the environment. Every stage of generative AI’s existence – from its training, public usage and performance improvements – requires significant energy, leading to increased carbon dioxide emissions. This is due to the data centres that house the hardware required to run and train the different AI models. While data centres existed long before generative AI, they are now constructed faster than ever because of the energy required to power and sustain the technology. Training AI alone can generate approximately 550 tonnes of carbon dioxide due to the electricity needed to run it. Furthermore, when generative AI is used (for ChatGPT specifically), it uses 10 times more electricity than a normal web search. Generating images and art using AI uses even more energy than generating text. Water usage is another concern, as large amounts are needed to cool data centres by absorbing excess heat.

There is another issue with AI art: it could consume and destroy itself. The large language models used to train generative AI are sourced from the internet. AI regurgitates the information it takes into a new output, which can be posted back into the internet where it got its knowledge from. This means that there’s a chance that AI will start training itself with the very same synthetic data it’s made – ie, it will start to eat itself. Recently coined as the Model Autophagy Disorder (MAD), this leads to ‘model collapse’, destroying the very foundation that AI is built upon. In text outputs, this leads to the AI spouting gibberish and incoherent sentences, while in image/art generators it leads to blurry, unidentifiable photos that may be unrelated to the prompt given. The AI will go ‘mad’ once it eats itself – a fitting outcome, and a cautionary parable.

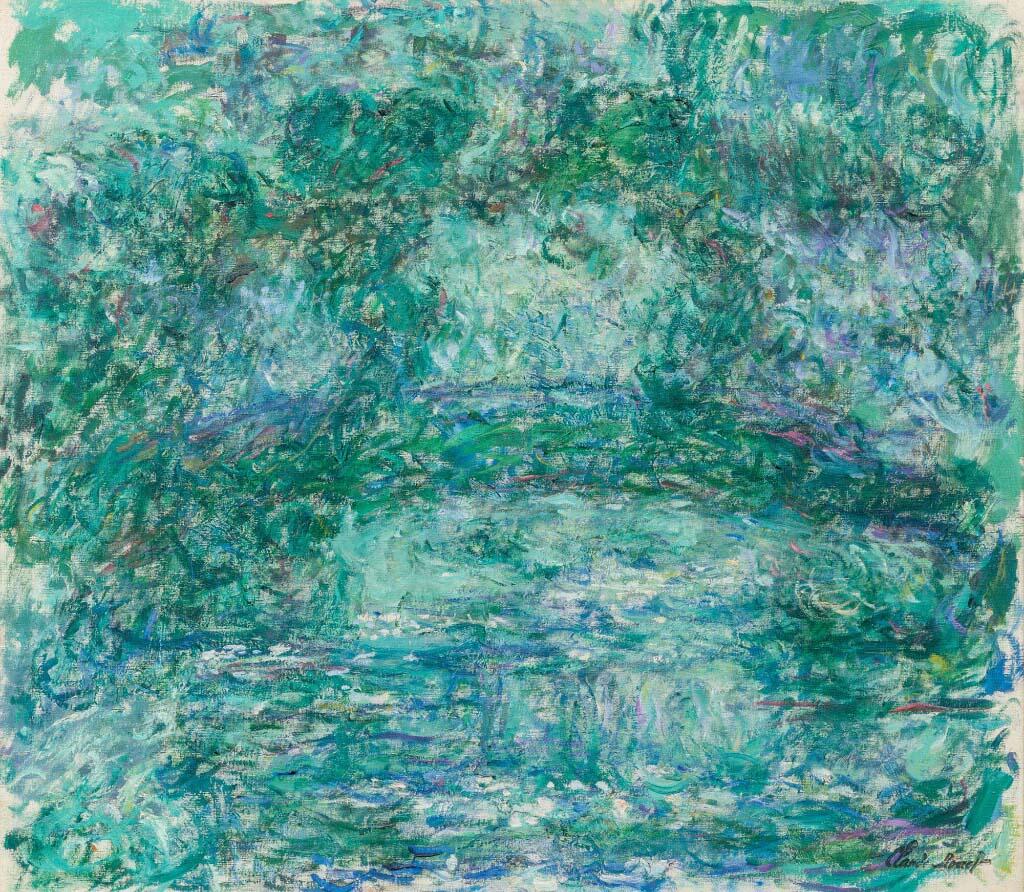

In a positive light, the surge of AI-generated art may actually help artists in a way. While it is true that there is the constant threat of AI replacing artists, there will always be value in art that is made by a human being. Throughout history, handmade works or crafts always had higher value than machine-made ones, and the same can be said in art. AI art may just start an era of increased value and appreciation for the human touch and labour in art – recognising the artist’s brushstrokes, fingerprints, mistakes: details that make their art irrefutably human.

In saying this, I see and think of art as a form of communication more than anything. You simply cannot communicate if you haven’t learned the language. AI art is the equivalent of saying random vocabulary words of several languages, hoping to form a coherent sentence. Its use is unfair, and harmful to artists. I’m positive that with generative AI’s rapid progression, it will and already is able to create art and images that are good enough to pass as manmade. However, this does not eliminate the other issues with its use, and if anything makes it worse, as it can be used for malicious purposes even more than it already is.Ultimately, we should all be asking ourselves if we want future generations to only have seen AI art and not experience the beauty and awe of art made with human effort, thought and skill.