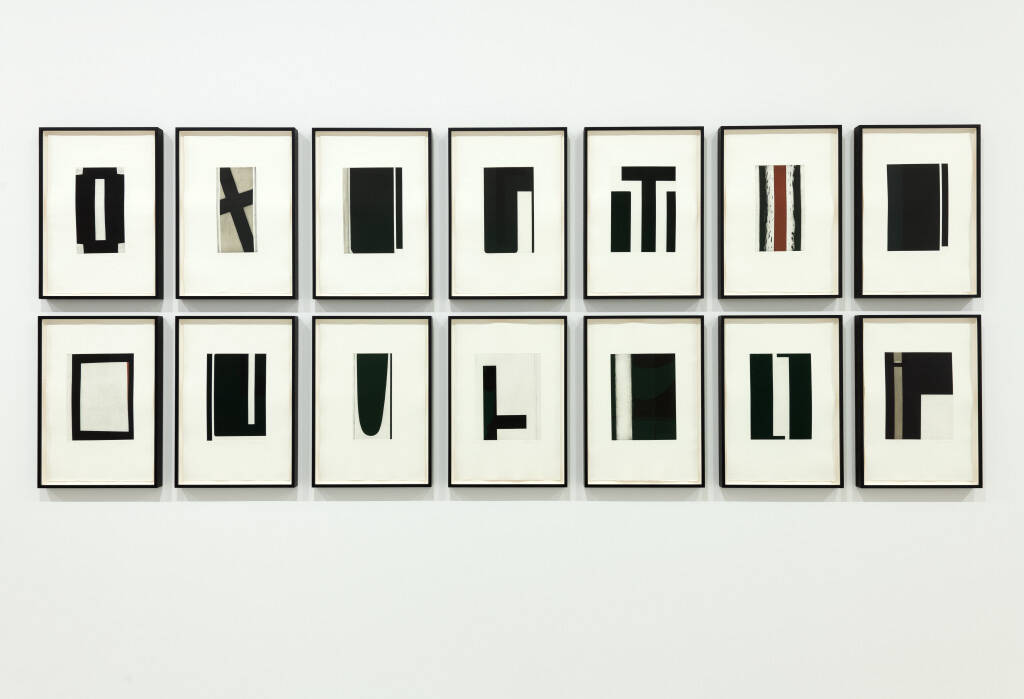

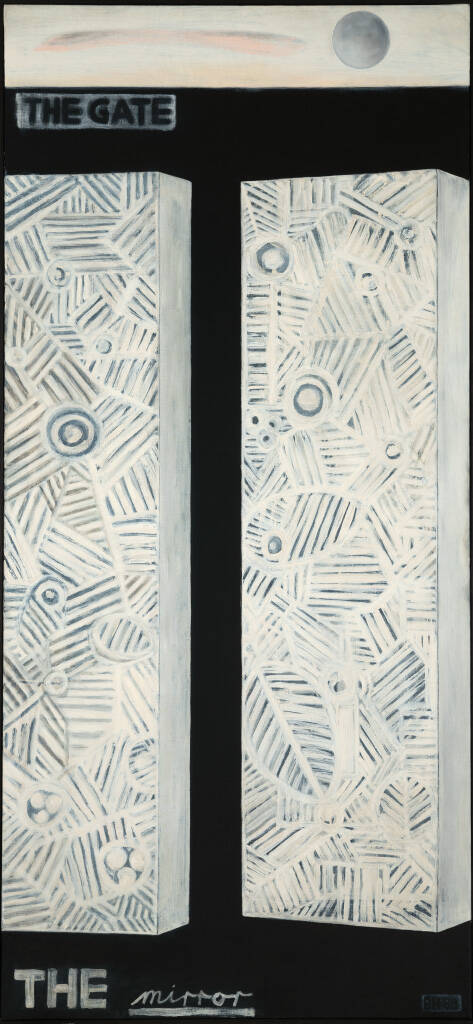

The Stations of the Cross recounts Christ’s final journey towards death, imaged in a sequence of 14 episodes.

My initial engagement with this subject was made at the height of the global HIV/AIDS pandemic, when I came to recognise this perennial religious story as a ready-made narrative for what was happening in my own world. The narrative of a young man judged in a morning, dead by afternoon.

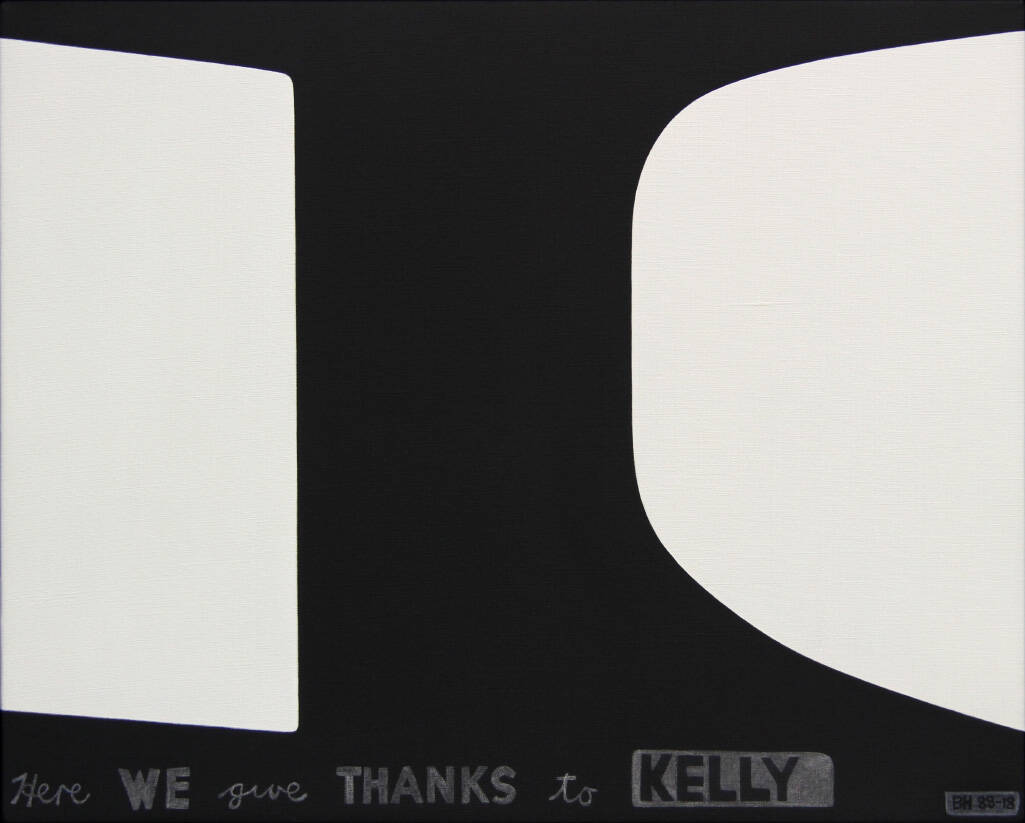

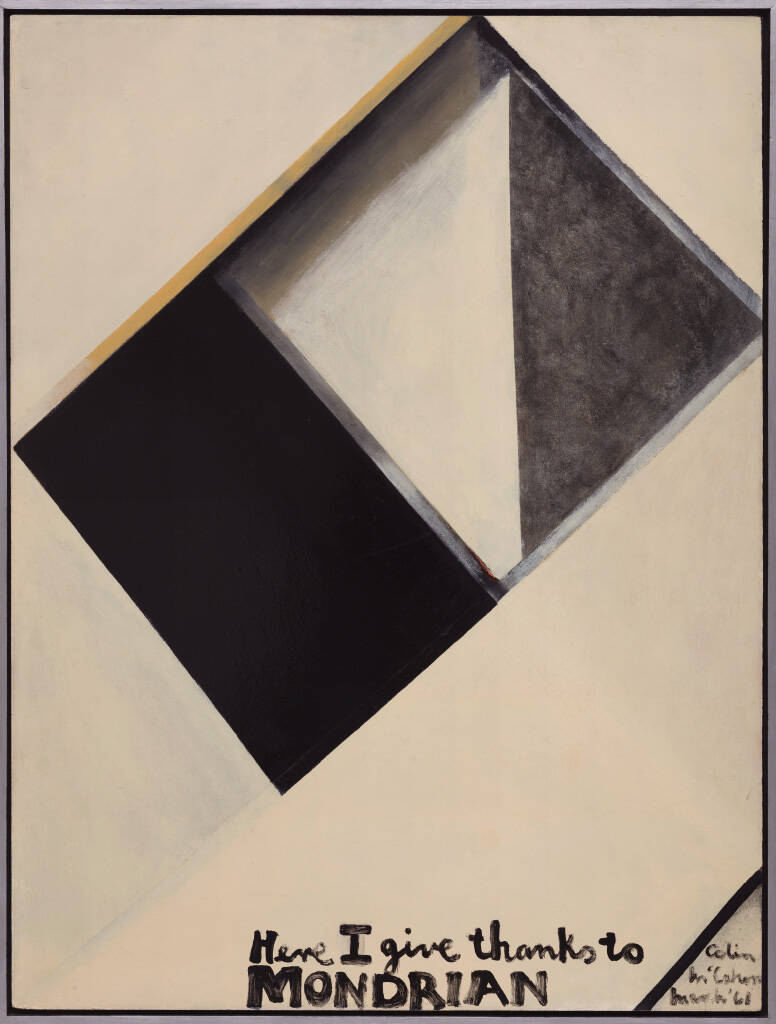

My 1989 series of The Stations was inspired by numerous art-historical explorations of this subject, most significantly Colin McCahon’s rendition, The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, 1966, in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, and a series of large abstract paintings by his American peer, Barnett Newman, from 1958–66.

While my 1989 series are resolutely abstract, I did attempt a connection with the subject both symbolically and psychologically. In the sequence of events Christ falls three times under the weight of his cross (Stations no. 3, 7, 9); with each fall his ego is diminished, so by the time he is nailed up (Station no.11), he is becoming tired of his burden and a little more resigned to his fate. A young person going to death is far more resistant, resentful of an early exit; an older person moving toward death is starting to tire of the flagging body.

There are two acts of kindness in the story. In Station no.5, Simon helps carry the Cross; we all carry the burden of each other’s death. In Station no.6 Veronica wipes the face of Christ, usually portrayed historically as a spot of blood on Veronica’s hanky as she presses her cloth to his face.

In my 1989 series I represent no. 6 as a river of blood. As context, in relation to the AIDS pandemic, blood had become bad – the 'blood rule', for example, had come into sport and a much wider social context.

In the catalogue for his 1972 survey exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery, McCahon stated that he felt his Fourteen Stations of the Cross was still too abstract. As an artist responding to these works, I questioned his reserve.