Kees and Tine Hos and the New Vision Gallery in Auckland were crucial in nurturing Gordon Walters’ new abstraction. His seminal exhibitions of 1966 and 1968 – Walters’ first since 1949 – were held there. Edited extracts from Chapter 3, ‘New Visions’, in Leonard Bell’s Strangers Arrive: Emigres and the Arts in New Zealand 1930–1980 (Auckland University Press, 2017) characterise the cultural importance of the New Vision Gallery.

Kees (Cornelis) Hos (1916–2015) and his wife Tine (Albertine, 1918–1976), post-World War II immigrants from the Netherlands, and their New Vision Gallery were key figures in the massive advances in New Zealand’s visual culture from the mid-1950s to the 1970s and beyond. The gallery’s name was not random. ‘New Vision’ derived from the term deployed by László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian-born, cosmopolitan Bauhaus teacher in Germany, a seminal modernist theorist and cross-media artist. His book The New Vision (1930) promoted new ways of seeing, thinking, making objects and using materials, which would, ideally, lead to necessary new states of consciousness for the betterment of society.[1] The enormously influential Bauhaus practice was multidisciplinary. It did not distinguish hierarchically between the fine and applied arts, or arts and crafts. Such was the New Vision Gallery’s practice, too. Painting, pottery, weaving, jewellery, sculpture and photography were all exhibited, sometimes in joint shows, like Patricia Perrin’s pots and Hos’s prints (1964).

By contrast, in mid-20th-century New Zealand society the traditional value distinctions between the fine arts and implicitly lesser crafts were still firmly in place. Among New Zealand’s ‘avant-garde’, painting and sculpture were privileged, with photography and the crafts rarely considered as fine art. Bauhaus ideals migrated to New Zealand with Hos and other Continentals, such as Frederick Ost, Gerhard Rosenberg, Helmut Einhorn, Theo Schoon and Imric Porsolt.

Migrating from the Netherlands in 1956 Kees and Tine, a weaver, first opened the New Vision Craft Centre in Takapuna, Auckland, while Kees worked for his sponsor, artist Ron Stenberg’s advertising agency, for two years. [2] Hos then lectured part-time at the Elam School of Fine Arts at Auckland University College, where he was struck by how little art-historical knowledge the students had.[3]

The New Vision Gallery shifted to a ground-floor shop in the now-demolished Edwardian His Majesty’s Arcade off downtown Queen Street in 1961.[4] In 1965, when the lease of the upstairs became free, they opened a further gallery for painting, sculpture and prints.

Kees and Tine Hos were ardent advocates for the visual arts. For many years a teacher at the Rotterdam Academy of Arts, Kees had studied at the Hague Royal Academy of Fine Art, one of the oldest art schools in Europe, founded in 1682. Bauhaus ideas and practices were promoted there. Pre-war German-Jewish refugee Paul Citroen, who taught at the academy, was a former Bauhaus student. He was also closely associated with Dada, and owned paintings by Klee and Kandinsky (both of whom taught at the Bauhaus). Citroen inspired Hos.[5] He became intensely committed to the view that ‘modern principles’ in art were a necessary component in any emergence of a new, equitable socio-political order.[6]

Hos was deeply concerned about the kinds of art society needs. While fighting for modernism, he recognised the merits of the traditional. He brought an encyclopaedic art knowledge and a rarely found professionalism to this country’s art world, as well as first-hand experience and understanding of interwar and post-war modernism in Europe. He and Tine supported and mentored numerous artists, actual and aspiring.

Given the wide range of activities New Vision generated and works it exhibited, the Hoses (along with Peter McLeavey in Wellington and Barry Lett and Rodney Kirk Smith from 1967 in Auckland) were surely the most influential gallerists in a crucial period of cultural change in New Zealand. The New Vision Gallery was the place for the visual arts and crafts in Auckland until the mid-1980s. It hosted cutting-edge exhibitions by such artists as Gordon Walters, Theo Schoon, Don Driver, Rudi Gopas, Louise Henderson, Philip Trusttum, Tony Fomison, Barry Cleavin and Ross Crothall, a neo-Dadaist little understood in New Zealand.

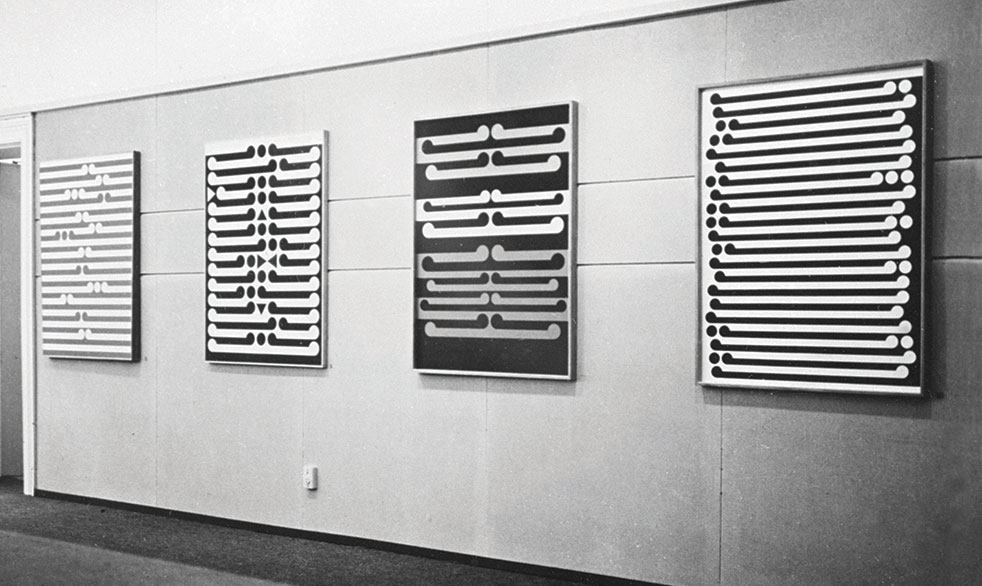

New Vision Gallery letters reveal that Kees and Tine communicated with just about everyone in the arts in New Zealand. They supported the new and experimental, and offered a lively social venue for artists and enthusiasts. New Vision was internationalist as much as local in orientation at a time when nationalist imperatives urging distinctively New Zealand art were strong. Hos also got contemporary New Zealand-made art out into the world; to Australia and the USA, for instance. The gallery provided a home for abstraction when that was rare. Most notably, its 1966 and 1968 shows of Gordon Walters’ hard-edge, ‘geometric’ abstracts were ground-breaking; effectively constituting a paradigm shift in how art in New Zealand could function and be understood. Previously Walters was alienated from mainstream visual culture, a kind of stranger in his homeland. In 1968 visiting British critic Robert Melville wrote an article on New Zealand art for Architectural Review, in which he singled out Gordon Walters’ painting as the best he encountered there.

The New Vision exhibition brochures were excellently designed with succinct, well-written comments, usually by Kees, and were at that time the best in New Zealand. Kees and Tine aimed to communicate widely, and they did. New Vision celebrated diversity and difference; correlates of open-mindedness and tolerance. Hos’s art writing is lucid and precise. For instance, on the occasion of a joint exhibition with French-born painter Louise Henderson at the John Leech Gallery in 1961 he eloquently asserted the renewed importance of the handmade, whether prints, weaving, pottery or painting, in a world increasingly dominated by mass-produced objects: ‘Their anti-individual, mechanical character tends to dehumanise our life . . . during the last 50 years . . . artist and craftsman have revolted against this degenerating tendency in our life . . . printmaking today is one of those islands of very human hand production’.[7]

Hos was also a brilliant artist. He characterised his own printmaking here as the most creative period of his life, in which he freely explored techniques, materials and processes: ‘new graphic media and methods . . . open up fresh horizons’.[8] His works are exemplary modernist pieces on a level of sophistication rarely found in New Zealand then; formally and visually self-sufficient and emotionally nuanced and rich in connotations. Hos aimed for freedom of expression (against conformity). He sought to visualise ‘what was beyond words’, the ‘indefinable’ in thought and feeling, as well as celebrating the autonomy and expressivity of means and media in their own power, so we really see and feel.[9]

Hos’s art regularly generated critical superlatives in the 1960s. For instance, in 1964 the New Zealand Herald art reviewer ‘B. B.’ (Beverley Simmons) wrote, ‘Artist Kees Hos makes magic with a mangle.’ He was ‘the most inventive and accomplished printmaker working in New Zealand today . . . [the] main force in the revival of interest in the graphic arts’.[10]

Kees Hos, It Happened 1967

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1967

Yet there are few pieces by Hos in New Zealand’s public galleries. Is this a consequence of his lack of concern with ‘New Zealandness’ and the putative particulars of place, as well as his cosmopolitan orientation? Except for a few generalities in an early 1970s account of prints in New Zealand, Hos was not written into the standard histories.[11] Yet as an artist, gallerist and catalyst Hos’s impact on the visual arts in New Zealand during his 15 years here was probably unequalled. For Gordon Walters the New Vision Gallery offered a new beginning.

[1] It was originally published in German as Von Material zu Architektur (Munich: Albert Langen, 1929). The first English edition was titled The New Vision: From material to architecture (New York: Brewer, Warren & Putnam, 1930).

[2] Kees Hos, artist’s statement, c.1962, Auckland Art Gallery library file. Oral History Interview Project: Kees Hos, interviewed by Damian Skinner, in Moe, Victoria, Australia, February 2000, as part of his Visual Culture in Aotearoa Archive, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Archives, CA000631.

[3] Oral History Interview Project: Kees Hos.

[4] See Joanna Trezise, ‘The Artists of the New Vision Gallery 1965–1981’, master’s thesis, University of Auckland, 2007; Joanna Trezise, New Vision: The New Vision Gallery 1965–1976, exhibition brochure, Gus Fisher Gallery, University of Auckland, 2008.

[5] Oral History Interview Project: Kees Hos.

[6] As above.

[7] Kees Hos, ‘Printmaking – New Aspects of Ancient Craft’, Auckland Star, 13 October 1961.

[8] Oral History Interview Project: Kees Hos.

[9] As above.

[10] B B, ‘Picture of the Week: “Pursuit” by Kees Hos’, New Zealand Herald, 28 November 1964.

[11] Hamish Keith described Hos as ‘a superb technician. He aims at exploring the expressive and creative potential of printmaking.’ Auckland Star, 18 November 1964.

Thanks to Auckland University Press and Leonard Bell for permission to publish.

Image credit:

Gordon Walters: Paintings 1965, 1966 (installation view: New Vision Gallery, Auckland)